Congratulations to Neil Denby, whose Roman military adventure, Decanus, is out now!

Decanus is the second book in the Quintus Roman Thrillers series.

Julius Quintus Quirinius and his cohort sail to the mysterious land of Britannia. They have been sent on a mission to scout out the savage country and battle the local tribesman to pave the way for their emperor.

But before they can land, a violent storm scatters their ships, separating Quintus, newly promoted to Decanus, from some of his comrades. In seeking them, he encounters Britons who may be friend or foe.

Betrayal is in the air when he discovers the missing legionaries have been captured by a local tribe. And the tribesmen are not willing to release the Romans alive.

Quintus is prepared to rescue his men or die in the attempt. His oath demands it. But can the legionary training of the Roman soldiers defeat the fierce foreign tribesmen?

Or will Quintus’ first foreign mission be his last?

Congratulations to Graham Brack, whose darkly humorous murder mystery, Murder in Maastricht, is published today!

Murder in Maastricht is the seventh historical murder investigation in the Master Mercurius Mystery series: atmospheric crime thrillers set in seventeenth-century Europe.

1686, The Netherlands

After getting Master Mercurius jailed and nearly put to death with one of his schemes, the Stadhouder, William of Orange, has finally left Mercurius in peace.

But Mercurius is not able to remain in Leiden for long. A friendly debate on the sin of witchcraft has been proposed between the University of Leiden and the University of Leuven. And the scholars are to meet part-way in the city of Maastricht.

When researching the local witch trials from 70 years ago, Mercurius comes across astonishing charges that could not possibly be true.

But the opposing side brings forth a witch-finder as a witness who is adamant that the women he charges bear the signs of the devil.

Before the debate can continue, the witch-finder is found brutally murdered. His body was left inside the library, locked from the inside with no other available exit.

Could this be the work of Satan? His wrath provoked by the investigation into local witch trials?

Or is the culprit someone grounded much more in reality…?

Congratulations to Jane Cable, whose captivating time-shift romance, The Lost Heir, is published today!

The Lost Heir is the second book in the Cornish Echoes Dual Timeline Mystery series.

Cornwall, 2020

Teacher Carla Burgess is using her time in solitude to revaluate her life. She loves living on the beautiful Cornish coast, but she no longer enjoys her job, and it’s certainly time to kick her on-off boyfriend, Kitto, into touch.

With lockdowns forcing her to spend most of her days indoors at her parents’ family farm, she joins her father in researching their family history, and she discovers the first Burgess to farm Koll Hendra was actually a smuggler. And when Carla finds a locked Georgian tea caddy in the barn, the secrets of the past start to encroach on the present…

Cornwall, 1810

Harriet Lemon’s position as companion to Lady Frances Basset has been the ideal cover for their clandestine romantic relationship. But when Frances is raped and falls pregnant, their perfect happiness is shattered. The lovers are desperate to remain together, but they will need to conceal Frances’s baby.

They hope to hide the pregnancy and place the baby with adoptive family, but the only person who may be able to help them is Frances’s childhood friend, William Burgess, a notorious smuggler. William has secrets of his own he needs to protect. Will he be willing to risk his own neck for the sake of the two lovers?

Congratulations to D. R. Bailey, whose page-turning World War II adventure, A Fool’s Errand, is published today!

A Fool’s Errand is the second book in the Spitfire Mavericks Thrillers series: action-packed aviation adventures set during the second world war and featuring a team of vigilante pilots.

The Battle of Britain is over, and RAF Fighter Command turns its attention to France.

Flying Officer Angus Mackennelly and the rest of ‘Maverick’ Squadron 696 are engaged in tactics to lure the Luftwaffe into battle.

But Angus has grave misgivings about the orders he has been given, which are justified when he loses a brand-new pilot on their first incursion.

And the squadron is dealt another blow when one of their pilot officers is discovered dead in the hangar.

The inquest rules the death a suicide, but Angus is certain something more sinister has happened.

In between bouts of furious dogfights in the skies, Angus and his good friend Flying Officer Tomas Jezek work tirelessly to investigate the murder.

While they risk their lives fighting a deadly foe, could the real threat be coming from an enemy within? Are the Spitfire Mavericks being targeted by someone who is supposed to be on their side…?

Congratulations to Natalie Kleinman, whose captivating Regency romance, Some Day My Prince Will Come, is published today!

Having suffered at the hands of an unscrupulous suitor during her first season in London, twenty-one-year-old Rebecca Ware has vowed to leave her ordeal in the past and is now embarking on her second season.

Though she is wary of opening her heart, Rebecca soon finds herself drawn to Comte Hugo du Berge, a handsome French nobleman who has recently arrived in London.

As the season progresses and Rebecca and Hugo find themselves thrown into closer proximity, their warm and easy friendship deepens.

However, with a long-buried family mystery to unravel, it seems that Hugo is not in a position to settle down. And when he prepares to return to France in search of answers, Rebecca begins to worry that she has lost her heart to a man she may never see again…

Congratulations to Adele Jordan, whose captivating espionage adventure, The Traitor Queen, is out now!

The Traitor Queen is the fifth book in the Kit Scarlett Tudor Mysteries Series.

1586

Female espionage agent, Kit Scarlett is stationed at Chartley Castle, where Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, is under house arrest for plotting against the English Queen Elizabeth.

Kit helps Sir Francis Walsingham’s top codebreaker, Thomas Phelippes, as they intercept Mary Stuart’s communications with her conspiring supporters.

And when they have the proof that Mary Stuart has sanctioned Queen Elizabeth’s assassination, Kit races to deliver the message to Walsingham.

But before they can persuade Queen Elizabeth to sign Mary Stuart’s death warrant, the Scottish queen escapes.

And as Kit delves deeper into her mission, she finally discovers answers about her own past that shock her to her core.

With Queen Elizabeth’s life now in imminent jeopardy, can Kit find Mary Stuart and bring her to justice?

Even if Kit achieves her task, will she find the London she returns to is no longer the home she once thought it was…?

Congratulations to Linda Stratmann, whose atmospheric historical mystery, Sherlock Holmes and the Legend of the Great Auk, is published today!

Sherlock Holmes and the Legend of the Great Auk is the fifth Victorian crime thriller in the Early Casebook of Sherlock Holmes series.

London, 1877

The unveiling of a new specimen of the extinct Great Auk leads to accusations of fraud against the British Museum and a ferocious attack on the exhibit by ornithologist Charles Smith.

Sherlock Holmes is tasked with saving the reputation of the museum, but before long, Smith is found murdered.

Police think it was a random robbery gone wrong but when Holmes examines the crime scene, he is sure there is more to it.

Aided by his loyal friend Mr Stamford, Holmes is determined to discover if the museum has something to hide.

Is there more to the legend of the Great Auk? Why has this exhibit attracted so much controversy?

Could more lives be in danger…?

Congratulations to David Field, whose gripping nautical adventure, Pirates and Patriots, is out now!

Pirates and Patriots is the first novel in The New World Nautical Saga Series: historical adventures set during the reign of Elizabeth I and beyond.

England, 1554

Fifteen-year-old Francis Drake is realising his dream of sailing on the open seas. After training with his cousins William and John Hawkins in their naval business, he takes his first commission upon the Bonaventure.

But when disaster strikes the ship and Francis saves the men with his quick-thinking, he makes an enemy of the captain, who threatens to charge Francis with mutiny.

Francis must seek a new path to make his fortune and he joins with the Hawkins brothers to search for glory in foreign lands.

But trading on the world stage is already being dominated by Spanish and Portuguese explorers and so Francis must act quickly if he wishes to make his mark.

And as one Tudor queen makes way for another, and Spanish relations grow ever tenser, Francis Drake may soon be needed to help save his country from the threat of war…

Congratulations to C. P. Giuliani, whose absorbing espionage adventure, Death in Rheims, is published today!

Death in Rheims is the third book in the Tom Walsingham Mysteries series: spy thrillers set during the Elizabethan era in Tudor Europe.

Tom Walsingham has been sent to France by his spymaster cousin, Sir Francis.

One of Sir Francis’s French informers has recently died in suspicious circumstances and Tom has been dispatched to investigate the death.

The dead man’s daughter is sure her father’s death was quite natural – but this doesn’t mean there aren’t strange circumstances surrounding it.

The informer lived in Rheims, close to a local English college where Catholic exiles are known to train for forbidden priesthood, and Sir Francis’s current plant at the college – a fiery young poet named Kit Marley – claims at least one of the young men has been murdered.

With yet another bout of civil war looming over France, and everyone pursuing their own agenda, Tom has his work cut for him, with plenty of aliases, betrayals and lies to disentangle.

And with relations still tense between the French and English, he must be careful not to betray his true identity and end up as the next victim…

Was the English informer targeted? Is there a serial killer at large?

And can Tom prevent any more deaths in Rheims…?

Congratulations to Natalie Kleinman, whose enchanting Regency romance, The Wishing Well, is published today!

Ever since the deaths of her fiancé and her father, Harriet Lambert has thrown herself into the management of her family’s estate to cope with her grief. Though time has eased her sorrow, she has had little opportunity to once again pursue romance.

But when she is called on to accompany her younger sister, Amabel, to London for her introduction into respectable society, Harriet finds herself caught in a flurry of social engagements. And when she meets Major Brew Ware at a soirée, the two form an immediate connection.

Having experienced tragedy at an early age, Brew understands the significance of Harriet’s loss. With their shared interests and honest approach, their friendship continues to flourish as the season wears on.

Though no man has turned her head since she lost her fiancé, Harriet is aware that her affection for Brew is growing stronger. And as she tentatively considers her future, she must now decide whether she is prepared to take another chance on love…

Congratulations to Laura Martin, whose gripping historical murder mystery, Death of a Lady, is published today!

Death of a Lady is first book in the Jane Austen Investigation series: thrilling Regency-era murder mysteries with a tenacious literary heroine working as a female sleuth.

1795, Hampshire, England

Jane Austen and her family are delighted to be attending Lord Wentworth’s ball. The event has been at the centre of village gossip after it was announced Wentworth was holding a ball to celebrate the return of his brother, who went missing in India many years earlier and had been declared dead.

At the ball an old friend, Emma Roscoe, bumps into Jane and tells her she saw something she shouldn’t have. She asks Jane to meet her at ten o’clock in the library to discuss it.

Delayed by dancing with the charming Mr Tom Lefroy, Jane is late to meet to her friend.

But when she arrives, she finds the body of Emma Roscoe lying on the floor with a dagger sticking out of her chest.

Distraught and feeling horribly guilty, Jane is determined to help with the investigation into Emma’s murder.

Was it a coincidence that the murder happened on the night of Lord Wentworth’s brother being reintroduced to society? What did Emma see that was worth killing her over?

And could more people be in danger?

With the help of her sister Cassandra, Jane must use her wit and intelligence to get to the heart of the mystery.

Congratulations to Richard Kurti, whose thrilling Renaissance murder mystery, Palette of Blood, is out now!

Palette of Blood is the second book in the Basilica Diaries Medieval Mysteries: historical thrillers set in fifteenth-century Rome and featuring a brother and sister investigative duo.

1503, Rome

Power has shifted among the great families, and a new Pope has been elected.

Julius II is determined to cement his place in history by redesigning the magnificent St Peter’s Basilica and he issues a challenge to the leading artists to submit their designs.

Aware that there are rich pickings to be had from such an ambitious project, Rome’s most powerful families each back different artists, hoping to get a monopoly on valuable building contracts.

But before a winner is picked, a shocking murder disrupts proceedings.

Prominent lawyer Antonio Ricardo is found brutally dismembered next to a magnificent work of art he commissioned.

And the killings don’t stop there…

Is one of the famously ruthless families behind the killings? Could it all be a dark campaign to scare off the rival bids?

Head of Security at the Vatican, Domenico Falchoni and his astute sister Cristina are determined to get to the bottom of the mystery.

But with the reputations of the most powerful families at stake, can they stop the deaths without putting their own lives on the line…?

Congratulations to David Field, whose absorbing historical saga, The Conscience of a King, is published today!

The Conscience of a King is the final instalment of The Medieval Saga Series – thrilling action-packed adventures set during and after the Norman Conquest.

England, 1229

After fighting in the Albigensian Crusade in France, Simon de Montfort – a landless nobleman – arrives at the court of Henry III, hoping to re-establish his family’s claim to the Earldom of Leicester.

In pursuit of his goal, Simon soon proves his value to Henry as a military leader and political advisor, becoming one of the king’s most trusted men.

But discontent is building within the English court. Frustrated by the king’s preference for foreign nobles and his extortionate taxes to fund wars abroad, the leading barons are constantly on the edge of rebellion.

As a man with a strong sense of justice, Simon is dismayed by Henry’s treatment of the common people and the corruptibility of the English legal system. And as the barons’ anger seems set to boil over into armed conflict, Simon must search his conscience and decide how far he is willing to go to bring about reform…

Can Simon restore his family’s fortunes? Can he help lead England into a new golden age while retaining the king’s favour?

Or will his principles cost him his life…?

Congratulations to Adele Jordan, whose gripping espionage adventure, The Lost Highlander, is out now!

The Lost Highlander is the fourth book in the Kit Scarlett Tudor Mysteries Series.

1586, London

Covert espionage agent, Kit Scarlett, is once again tasked with defending Queen Elizabeth against an assassination attempt.

With the attacks on the queen’s life mounting, Kit and spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham know they need to find a firm link between these deadly plots and Mary Queen of Scots.

But Kit is also keen to investigate a more personal matter. Her espionage partner, Iohmar Blackwood, did not return from his last mission set by Walsingham and has not been seen for a year.

When Kit is given a task by Queen Elizabeth to deliver a letter to Mary Queen of Scots, a letter not to be read by officials or any political figure, she takes advantage of the opportunity search for Iomhar and find out what happened to him.

But she soon finds herself trailed by Mary Stuart’s supporters and her journey becomes fraught with danger.

Can Kit complete her mission? Will she find out what happened to Iohmar?

Or will she become a victim in the fight to overthrow the queen of England…?

Congratulations to Neil Denby, whose action-packed military adventure, Legionary, is out now! Legionary is the first book in the Quintus Roman Thrillers series.

17 BC

Julius Quintus Quirinius, like many citizens in the years after Rome’s civil wars, must volunteer with the Roman army or be sold into slavery.

Keen to prove his worth, he becomes a member of the IXth Legion, but after only six months his cohort suffer a brutal defeat, the result of stupidity and cowardice.

Cowardice in a legionary carries a heavy punishment: the sentence of decimation – to live or die at the whim of the gods with the unlucky ones clubbed to death by their fellow soldiers.

Ursus, the man killed in Quintus’ group, lays a heavy charge on the youth, asking him to look after the remaining men and to take care of his family back in Rome.

Keen to fulfil Ursus’ last wishes, Quintus helps lead his cohort south to defeat the tribesmen skulking in the mountains in the hope that the IXth legion’s reputation will be restored.

But if they win the fight, their reward may not be the prize they had hoped for… And it soon seems as if returning to Rome is further out of reach than ever…

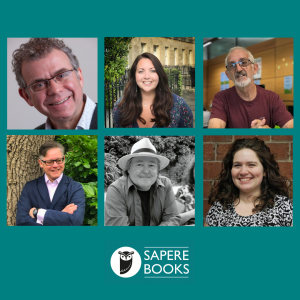

We are thrilled to be celebrating five years in business this month and we are incredibly grateful to all the writers, agents and literary estate holders who have helped us bring to market such a vibrant and diverse list of books.

Since launching Sapere Books in March 2018, our list has grown to include over six-hundred books by over one hundred authors. We have sold over 3 million books to date with 500 million pages read through Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited program.

In 2019, we employed our first full-time staff member, Natalie Linh Bolderston, who now holds the title of Assistant Editor, and in 2020, Matilda Richards and Helen Jennings both also joined our editorial team. They have all been essential to our ongoing success and we are over the moon that they are continuing the journey with us as we celebrate our first big milestone.

In 2020, we launched our non-fiction list, which includes classic works by authors such as E R Chamberlin, Sir Peter Gretton and John Bowle. And we are now pleased to announce that we are also hiring another staff member to help look after our burgeoning military history and military fiction list.

Since launching, we have focussed primarily on fiction, particularly historical fiction and crime fiction, and in 2021 we created our first historical writing contest, asking for entrants to submit a series outline loosely based on briefs we set. The response was so strong that as well as signing up five prize-winners we also signed ten more authors from the shortlisted entries.

We have always been keen to foster a community among our authors. In 2020, to combat some of the isolation due to the pandemic, we started running weekly Zooms for our authors to join and chat about their writing. These have become a valuable part of our ethos and we want to continue to make our authors feel welcomed, valued and part of the Sapere Books family.

We are also proud to announce that we have been certified Carbon Neutral since 2021 and we have created our own Sapere Books forest, planting a tree for every author that we work with.

We look forward to continuing to build strong relationships within the writing community and to publishing more brilliant genre fiction to capture the imagination of readers. Thank you again to everyone who has supported us and we hope you continue to love our books!

Amy, Richard and Caoimhe

Testimonials from four of the authors who launched with us in 2018:

David Field, author of the Medieval Saga series, the Tudor Saga series and many more

By one of life’s happy coincidences, I came across Amy Durant just when the publisher that had commissioned my first historical novel series decided to close down. Five years later I’ve published over twenty historical novels with Sapere, with ten more waiting to go.

When you become a member of the Sapere family, you’re all set for a rewarding writing career. If the quality’s right, you know that your latest ‘baby’ will be assured of a good home. They provide great editing, superb covers, expert marketing, regular royalty payments and guaranteed replies to your emails. Sapere authors have indeed been smiled upon by the patron saint of aspiring writers.

Keith Moray, author of the Inspector Torquil McKinnon series

Being published by Sapere Books has been a revelation for me as a writer. From the very first moment that Isabel Atherton, my agent at Creative Authors, arranged a chat with Amy Durant it has been a fabulous experience. Over the past five years, I have seen my backlist of fiction published along with five new novels, and I have three more under contract. Every aspect of book production from editing, cover design, publicity and marketing has been handled with flair and efficiency. On top of that, communication could not be easier or quicker, and Sapere Books have created a friendly atmosphere among all of the authors that makes me feel pleased to be part of the Sapere Books family. I could not be happier than I have been with Sapere Books, who are in my opinion without parallel in the publishing industry.

Linda Stratmann, author of The Early Casebook of Sherlock Holmes and the Mina Scarletti Mysteries

Becoming a Sapere Books author is like joining a warm and welcoming family, dedicated to providing the best for authors and readers. An experienced and hardworking team offers a soundly professional service, always on hand for support and advice. The last five years has seen Sapere grow and flourish, but never losing that personal touch.

Elizabeth Bailey, author of the Lady Fan Mystery series

Working with Sapere has been the most enjoyable and rewarding publishing experience in all my thirty-odd years as an author. That my career is flourishing is testament to the care and attention given to every book. Authors are encouraged to interact and support each other, which makes me feel part of a family, parented by the nurturing and talented Sapere team. Long may they reign! Oh, and we all love our covers!

Congratulations to Linda Stratmann, whose eerie historical mystery, Sherlock Holmes and the Persian Slipper, is published today!

Sherlock Holmes and the Persian Slipper is the fourth Victorian crime thriller in the Early Casebook of Sherlock Holmes series.

London, 1877

When medical student Mr Stamford is visited by his cousin, Lily, he is disturbed by the sinister tale she relates.

Lily’s friend, Una, has recently inherited an old country house and settled down to married life in Coldwell, a small Essex village. However, Una’s letters to Lily indicate that she is alarmed by her new husband’s secretive behaviour — especially when she discovers a gun in his drawer, tucked inside a Persian slipper. Fearing for her friend’s safety, Lily asks Stamford to pay Una a visit.

To his dismay, Stamford arrives in Coldwell to find that Una’s husband, John Clark, has been found dead, lying in bed with a gunshot wound in his chest. Close examination reveals that the bullet was fired from Clark’s own gun, through the toe of the slipper.

Stamford loses no time in alerting his acquaintance, Sherlock Holmes — an artful young sleuth — hoping that he can shed some light on Clark’s death.

As Holmes and Stamford begin to probe Clark’s past, it soon becomes obvious that he had plenty to hide. And when Holmes hears of further suspicious disappearances, he starts to search for the connection between the sinister mysteries…

Congratulations to Richard Kurti, whose absorbing historical mystery, Omens of Death, is published today! Omens of Death is the first book in the Basilica Diaries Medieval Mysteries series, set in fifteenth-century Rome.

1497, Rome

Wealthy merchant’s daughter Cristina Falchoni has a vision: to create a magnificent cathedral in the heart of Rome. Europe is in desperate need of a powerful unifying symbol, and a great basilica, built over the tomb of St Peter, will be a rallying point for Western civilisation.

With the help of her brother Domenico, as Head of Security at the Vatican, Cristina manages to persuade Pope Alexander VI to cleanse his conscience by reviving a decades old plan to construct a new basilica as a celebration of God’s greatness. Whatever bribery, corruption, lechery, or assassination lay in the Borgia Pope’s past, all would be forgiven; he could atone through stone.

But when a prominent aristocrat is found brutally murdered in a grotesque parody of the martyrdom of St Peter, Pope Alexander fears it is a divine warning, a message from God not to tamper with the revered shrine.

Realising that their dream of a glorious new cathedral is in jeopardy, Cristina and Domenico urgently start to investigate the grisly murder.

But as more ominous events torment Rome, they soon realise that whoever is behind these strange portents will stop at nothing to get their own way — even if it means killing the Pope himself.

With the Pope’s life in danger, can Cristina and Domenico uncover the truth before it’s too late? Or are they about to become the killer’s next targets?

Congratulations to Adele Jordan, whose page-turning espionage adventure, A Spy at Hampton Court, is published today!

A Spy at Hampton Court is the third book in the Kit Scarlett Tudor Mysteries Series.

Queen Elizabeth is gravely ill and her spymaster, Francis Walsingham, has received intelligence that there is a plot to assassinate her.

He sends his protégé Kit Scarlett and Scottish agent Iomhar Blackwood to gather information.

To their horror, they discover there is a plot to blow up Hampton Court Palace.

With Queen Elizabeth too unwell to be moved from the palace, it is imperative the plot is foiled as quickly as possible.

A search of Hampton Court is launched, with Iomhar leading the way, while Kit is given the task of guarding the queen.

Watching her queen fighting death and suspecting she has been poisoned, Kit soon realizes the threat could be within Hampton Court’s own walls…

Is there an enemy spy at the palace? Has gunpowder already been planted by an assassin? And is someone in Queen Elizabeth’s inner circle slowly poisoning her…?

Congratulations to Amy Licence, whose page-turning Tudor drama, Troubled Queen, is published today!

Troubled Queen is the second book in the Marwood Family Tudor Saga Series.

Escaping from her family’s scandalous involvement with Anne Boleyn’s circle, Thomasin Marwood is beginning a new life in the service of Queen Catherine of Aragon.

Thomasin is trying to forget Rafe Danvers, the man who stole her heart and then betrayed her, and when a group of Venetians arrive at court, she is drawn to the sophisticated Nico.

But a great danger is lurking. The dreaded sweating sickness has returned, which claimed the life of Catherine’s first husband, Prince Arthur, many years ago.

Catherine and her ladies are forced to flee, and their shared isolation with King Henry brings the couple closer again.

But Anne Boleyn will not let herself be forgotten.

Thomasin finds herself torn between new friends and old loyalties as Rafe comes back into her life.

Who will win Thomasin’s heart? Will she survive the dreaded sickness?

And will Anne Boleyn become victorious in her quest for the throne?

Congratulations to Stephen Taylor, whose absorbing dual-timeline mystery, The Mystery of Rufford Abbey, is out now!

When historian Toby Wyatt receives a collection of chronicles written by Brother Roger of Hathern — a medieval monk who lived at Rufford Abbey — he is plunged into a nine-hundred-year-old mystery.

The monk tells the story of Margaret of Wellow, a fifteen-year-old girl who was accused of witchcraft after experiencing strange visions. After careful reading, Toby realises that Margaret seems to have been able to see into the future.

Back in the present day, a woman vanishes without a trace and the police are drawing a blank. Toby’s research takes a bizarre turn when he discovers a link between the woman’s disappearance and Margaret’s visions.

Faced with a seemingly impossible solution to the mystery, Toby begins to question his instincts. And as the past collides with the present, he must decide whether he can put his faith in a girl who has been dead for nine-hundred years…

Congratulations to Patrick Larsimont, whose thrilling wartime adventure, The Lightning and the Few, is published today!

The Lightning and the Few is the first book in the Jox McNabb Aviation Thrillers series: action-packed, authentic historical adventures following a RAF pilot during the second world war.

Scotland, 1939

When Jox McNabb is expelled from school he is forced to look to his future.

Inspired by the sight of a Hurricane flying over him, he becomes determined to join the RAF.

And after basic training, Jox is posted to RAF Montrose with the growing group of other recruits he has met along the way.

Battling the bleak Scottish elements and finding themselves immediately thrown in at the deep end, the lads struggle to keep up with the training.

Many are deemed unfit for service, and after tragedy strikes, Jox questions if he’s got what it takes.

Can Jox earn his wings to face Blitzkrieg and defend his country in its hour of need? Does he have the courage and skill to become one of The Few? Will he beat the odds to survive his first battle?

Congratulations to David Field, whose gripping historical saga, The Absentee King, is published today! The Absentee King is the fifth book in the Medieval Saga series.

Richard the Lionheart has been crowned King of England.

But his obsession with fighting in the Third Crusade sends him off to foreign lands.

The nation is left in a perilous state, with high public offices sold off, and trusted favourites left to rule during Richard’s absence.

Richard’s dissolute and envious younger brother John feels humiliated, not least when Richard declares his four-year-old nephew Prince Arthur to be his heir, and he causes unrest throughout the nation by enforcing harsh laws designed to keep the population under his iron fist.

Chief Justice, Earl William of Repton, is ordered to investigate the possibility that John is seeking to undermine his brother Richard’s rule.

And when news reaches England that King Richard has been captured, and is being ransomed by Henry VI of Germany, William becomes convinced that John is plotting to seize the English crown.

Will Richard be released? Will he return to claim his throne?

Or will John succeed in his mission to overthrow the absentee king…?

Congratulations to Justin Fox, whose thrilling wartime adventure, The Wolf Hunt, is out now! The Wolf Hunt is the second book in the Jack Pembroke Naval Thriller series.

1941

Lieutenant Jack Pembroke has found a new home and new love at the Cape, but it will all hang in the balance with the arrival of the enemy in South African waters.

With the Mediterranean all but closed to maritime traffic, and Rommel’s forces rampaging through North Africa, this sea route is vital to supplying the Allied forces in Egypt.

But German U-boats have been sent by Admiral Donitz from their bases on the west coast of France to cripple the convoy route.

Jack is put in command of a small anti-submarine flotilla in the Royal Navy base of Simon’s Town, South Africa.

But he has very little time to train his officers and men, and prepare his ships, for the arrival of the Nazi wolf packs.

With the Cape under attack, Jack has to escort a vital convoy from Cape Town to Durban.

But with the enemy U-boats lying in wait in the storm-ravaged waters, he’ll be luck to make it out alive…

Congratulations to C. P. Giuliani, whose absorbing Tudor espionage novel, A Treasonous Path, is out now!

Tom Walsingham is back in London, being groomed for intelligence work by his spymaster cousin, Sir Francis.

An anonymous informer has started sending letters from the French ambassador’s residence, claiming to have bribed the man’s secretary to pass on information.

The informer has discovered messages between the French and Mary, Queen of Scots, which could harm the English Queen Elizabeth.

When someone who works for the French Ambassador is killed in suspicious circumstances, Sir Francis sends Tom to investigate the matter – and to uncover the identity of the informer.

Tom must find a way into the French Ambassador’s good graces and make friends within his retinue without giving himself away.

And as the news from Scotland grow more and more alarming, it becomes imperative that Tom unveils the identity of the secret informer and exposes the intrigues at play.

Can Tom unravel the mystery and protect the Queen? Will he unmask the killer?

Or could he find himself the target of a deadly plot…?

Congratulations to J. C. Briggs, whose thrilling Dickensian adventure, The Jaggard Case, is published today!

The Jaggard Case is the tenth urban mystery in J. C. Briggs’ literary historical series, the Charles Dickens investigations, a traditional British detective series set in Victorian London.

With Superintendent Sam Jones away in Southampton on the trail of missing murderer Martin Jaggard, his wife, Elizabeth, enlists the help of Charles Dickens when her beloved servant, Posy, goes missing.

Meanwhile, Jones apprehends Jaggard’s mistress, Cora Davies, who is in possession of stolen jewels belonging to Jaggard’s murder victim, Sir William Pell.

But Jones is no closer to finding the man himself, so he returns to London where he believes Jaggard may be hiding.

Dickens and Jones discover that their separate cases both have links to Clerkenwell – a notorious haunt for criminals and forgers.

And when they suspect they are being followed, they realise Jaggard may be onto them.

Was Jaggard behind Posy’s abduction? Is the servant girl still alive?

Or will more victims be found dead in the mysterious Jaggard Case…?

Congratulations to Phillipa Vincent-Connolly, whose fabulous Tudor adventure, The Anne Boleyn Cypher, is out now!

The Anne Boleyn Cypher is the first book in the Timeless Falcon Dual Timeline series, a timeslip alternative history novel with a time-travelling protagonist set between the modern day and the Tudor period.

When twenty-year-old history student, Beth Wickers starts her second year of university, she has no idea that her whole world is about to be turned upside down.

Beth’s favourite lecturer gives Beth a box of books on Tudor history to borrow, and nestled among them is an ornate cypher ring with the letters ‘AB’ inscribed onto it.

When Beth tries the ring on, the unimaginable happens.

It carries her back through time to Hever Castle in 1521. And she is no longer in her professor’s office, but in the bedroom of none other than Lady Anne Boleyn.

Beth quickly becomes enchanted by Tudor England and is captivated by Anne. But she knows she can’t leave her loved ones behind forever.

Tormented by the knowledge of what will happen to Anne in the future, can Beth stop herself from intervening and rewriting history? Can she use the cypher ring to return home?

Or will Tudor life be too hard to leave behind…?

Congratulations to Keith Moray, whose gripping historical thriller, Death of a Poet, is published today!

Death of a Poet is the first book in the Ancient Egypt Mystery series.

Hanufer of Crocodilopolis, newly appointed Overseer of the Police in Alexandria, is keen to prove himself worthy to both the citizens of the city and to the Pharaoh, Ptolemy Philadelphus.

When an altar is desecrated with a poem intended to insult the Pharaoh and his wife, Queen Arsinoe, Hanufer and his trusted sergeant Sabu are tasked with discovering who committed the outrage.

As the poet himself, Sotades the Obscene, was recently executed, Hanufer sets about finding out who else is familiar with his poetry.

Before long another poet is found murdered – a poem by Sotades left near the corpse as a macabre calling card.

With a growing number of murders to be investigated, Hanufer must make his mark and solve the mysteries.

But just where — and how high up — will the clues lead him?

Did Sotades really drown? Is there a serial killer on the loose in Alexandria?

And can Hanufer appease both the Pharoah and the gods?

Congratulations to Graham Ley, whose captivating French Revolution saga, Heir to the Manor, is out now!

As the conflict in France rages on, the Wentworth family — Anglo-French aristocrats — must find their place in a changing world.

Staying with friends in Cornwall and Plymouth, young Amelia is widening her social circles at soirees and assemblies. Finding herself in the company of several eligible gentlemen, she begins to wonder whether romance is on the horizon.

After fighting in France, Justin has married Amelia’s friend Arabella and the two have settled down at Chittesleigh Manor, his Devonshire estate. However, Arabella still feels responsible for Amelia and vows to find a way to protect her from unscrupulous suitors.

Hailing from Brittany, Sempronie — Amelia and Justin’s mother — feels her birthplace calling her home, despite the dangers of returning. What’s more, there is a long-buried family secret that she must put right before it’s too late…

Congratulations to Linda Stratmann, whose gripping historical mystery, Sherlock Holmes and the Ebony Idol, is published today! Sherlock Holmes and the Ebony Idol is the third Victorian crime thriller in the Early Casebook of Sherlock Holmes series.

When a pugilist dies at a local boxing demonstration attended by medical student Mr Stamford and his acquaintance Sherlock Holmes, a post-mortem reveals the death is due to natural causes.

But when the corpse of another boxer is discovered clutching a small wooden carving – the ebony idol – Holmes begins to suspect that sinister forces are at work.

His suspicions seem confirmed when the companions hear about a previous death in the ring.

Tasked by the man’s widow to bring his killer to justice, Holmes and Stamford are swiftly drawn into their most curious case to date.

Click here to order Sherlock Holmes and the Ebony Idol

Congratulations to Adele Jordan, whose thrilling historical espionage novel, The Gentlewoman Spy, is published today!

What happens when the spymaster’s right-hand man turns out to be a woman…?

Sir Francis Walsingham, spymaster to the Tudor Queen Elizabeth has trained Kit Scarlett since she was a girl. Aware that she is able to infiltrate places that his male agents cannot, he sees her as an invaluable member of his team.

When Walsingham discovers that a rebel alliance is planning to overthrow Queen Elizabeth and put Mary, Queen of Scots on the English throne, he summons Kit immediately.

Together with loyal Scottish agent Iomhar Blackwood, Kit is tasked with finding out the full details of the treasonous plot.

Both used to working alone, Kit and Iomhar struggle to get along, but they must come together if they are to have any chance of stopping the deadly conspiracy against the queen.

Can Kit secure her place in a man’s world? Will she save Queen Elizabeth?

Or will her daring ultimately be her downfall…?

Congratulations to Coirle Mooney, whose enchanting Medieval drama, The Cloistered Lady, is published today!

Eleanor of Aquitaine has been arrested for rebelling against her husband, King Henry II of England.

Her loyal ladies-in-waiting, Alice and Joanna of Agen have fled to the nunnery at Fontrevault, where they are anxiously awaiting news of their queen.

Alice and Joanna struggle to adapt to their cramped new home at the Abbey. Each is secretly nursing a broken heart – and harbouring unholy desires.

Joanna left behind a lover, Jean, at Eleanor’s court in Poitiers, and Alice has long been in love with the queen’s daughter, Marie.

And as the days stretch on with no news, they both begin to fear the worst.

What has happened to Eleanor? Will Alice and Joanna be forced to remain at the Abbey indefinitely? And will they ever be reunited with the ones they love?

Click here to order The Cloistered Lady

Congratulations to

Nineteen-year-old Thomas Walsingham is thrilled to be working as a confidential courier, carrying messages between London and Paris for his illustrious cousin, Queen Elizabeth’s spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham … until everything goes wrong.

Tasked with escorting an English glove-maker to the French Court, Tom is also playing messenger for the Duke of Anjou, Queen Elizabeth’s French suitor, as well as carrying confidential instructions to the English Ambassador in Paris.

When French soldiers assault his convoy en route, Tom loses a letter he had sewn into his clothes. And the next morning, the glove-maker is found stabbed to death.

Determined to prove himself, despite failing so disastrously in his mission, Tom pushes on to Paris, but when he gets there, he discovers the glove-maker may not have been who he said he was.

Certain the queen may now be at risk, Tom is determined to report back to Sir Francis, but he cannot afford to wait for official orders.

Who was the glove-maker working for? Why was he killed? Isolated and without a passport, Tom must travel incognito and return to the English court before anyone else ends up dead…

Click here to order Road to Murder

Congratulations to David Field, whose gripping medieval thriller, Traitor’s Arrow, is published today!

When King William Rufus of England is killed mysteriously during a hunting accident in the New Forest in 1100, his younger brother Henry, who had been present, loses no time in riding hard to claim both the Treasury and the crown.

Rumours quickly being swirling that Henry was himself responsible for Rufus’s death. One of Henry’s main accusers is his older brother Robert, Duke of Normandy, who believes the throne of England is his by right and threatens to invade from across the Channel.

King Henry entrusts the task of proving his innocence to Sir Wilfrid Walsingham, a Saxon-born knight who was elevated by Henry’s father, only to be cast by the perverted and tyrannical Rufus into a jail cell from which, after almost two years, few men could have emerged alive, or with their sanity intact.

Can Walsingham unearth the truth about Rufus’s death and clear his name? Or will England be torn apart by those in power…?

Click here to order Traitor’s Arrow

We are delighted to announce that we have signed a new dual timeline series set in the modern day and Tudor times by Phillipa Vincent-Connolly.

Told in authentic detail, the four-book series explores the intrigue and plots within King Henry VIII’s court. The books include ingenious twists on Boleyn family history, retold through a twenty-first-century history student’s eyes. The first instalment will be published later this year.

In Phillipa’s words:

“It’s very exciting to be working with Sapere Books on my first historical fiction series. The series is very special to me, as it includes appearances from some friends and colleagues of mine, who are featured as cameo characters from the modern day, with the history of the Tudor period also wound through, creating an exciting retelling of Anne Boleyn’s story. The narrative moves between the present day and the middle of Henry VIII’s reign.

“Set in South London and Queen Mary University of London, the first book follows an enthusiastic history undergraduate called Beth Wickers, who gets the shock of her life when her professor’s gold cypher ring opens up a mysterious portal that takes her to Tudor England and Hever Castle, where she becomes an integral part of Anne Boleyn’s life. She’s been warned not to meddle or risk changing history, but can she allow her dear friend to go on to become the second wife of King Henry VIII and to meet a horrific death? Can Beth save herself from the machinations of the Tudor Court, or will she meet the same fate as the queen to be? Only the ring has the answer.”

Amy Durant, publishing director of Sapere Books, commented: “I am thrilled to be working with Phillipa on these books, which breathe new life into the Tudor period. We are sure our readers are going to love the series!”

Click here to visit Phillipa’s website

We are thrilled to announce that we have awarded winners in all six of the writing competition briefs that we set last year.

Top row: Richard Kurti, Laura Martin, Neil Denby. Bottom row: Patrick Larsimont, Bob Robertson, Rachel McDonough.

Each chosen author has won a five-book contract to work on the series they submitted for.

Screenwriter Richard Kurti has won The Medici Murder Mystery series brief.

The Second World War Aviation Thriller series brief was won by debut author Patrick Larsimont.

Established romance author Laura Martin scooped the Jane Austen Detective series brief.

Ghost-writer Bob Robertson snapped up the Age of Sail brief.

Academic author Neil Denby scooped the Ancient Rome Historical thriller brief.

And American author Rachel McDonough won the Tudor Maid Diaries series brief.

The quality of the entries were so strong that we have also awarded honourable mentions in nearly all of the categories and we are speaking to the shortlisted authors about writing other historical series for us based in the time period of their submission.

The shortlisted authors are:

Donna Gowland and Leann McKinley for the Jane Austen brief.

Daniel Colter and Ava McKevitt for the Ancient Rome brief.

David Bailey, David Mackenzie, Tony Rea and Suzanne Parsons for the WWII brief.

Kate MacCarthy for the Medici brief.

Alice Campbell, Angela Ranson, Katharine Edgar, Valerie Boyd and Maria Hoey for the Tudor brief.

Following the success of the first competition we are hoping to run the competition again later this year with a fresh set of writing prompts.

Congratulations to Natalie Kleinman, whose captivating Regency romance, Love’s Legacy, is out now!

When her father — a countryside reverend — dies suddenly, young Patience Worthington is left with no home and little money. In urgent need of support, she is forced to seek out her estranged uncle, a viscount at the vast Worthington Place.

When her father — a countryside reverend — dies suddenly, young Patience Worthington is left with no home and little money. In urgent need of support, she is forced to seek out her estranged uncle, a viscount at the vast Worthington Place.

Patience arrives to find that her uncle has died and that the current viscount is her cousin, Gideon. After hearing her plight, he agrees to give her a home on the Worthington estate.

However, when Patience and Gideon learn the cause of the long-standing rift between the two sides of the family, they quickly begin to clash. Now too proud to accept his accept the viscount’s charity, Patience soon leaves Worthington Place to seek shelter with her late mother’s relatives in Bath.

With her kindness and beauty, Patience is an instant success in Bath society and regularly crosses paths with Gideon. Despite their differences, they enjoy each other’s company and form a tentative friendship.

But when dark secrets once again threaten their growing bond, the cousins begin to wonder whether they can ever leave the shadows of the past behind…

Click here to order Love’s Legacy

Congratulations to David Field, whose thrilling Medieval saga, Conquest, is published today!

It’s 1065 and the Saxon kingdom is under threat of invasion at both ends. From the north comes Harald Hardrada of Norway intent on pillage, while across the Channel, Duke William of Normandy is about to enforce his claim to the throne.

It’s 1065 and the Saxon kingdom is under threat of invasion at both ends. From the north comes Harald Hardrada of Norway intent on pillage, while across the Channel, Duke William of Normandy is about to enforce his claim to the throne.

Between the two lie the villages and townships defended only by part-time armies maintained by the Earls of Wessex, Mercia and Northumbria, barely united under King Harold Godwineson.

It falls to brave and determined young men like Will Riveracre and Selwyn Astenmede to stand firm against whichever marauding invader reaches them first.

But the initial battle could be the least of their worries as a new king ascends the throne – threatening to annihilate their traditions and customs forever…

Congratulations to Ros Rendle, whose breath-taking dual timeline saga, The Divided Heart, is published today!

Having recently suffered heartbreak, twenty-five-year-old Heather Rawlins is ready to give up on love. Her confidence in tatters, she seeks solace in her new job at The Beeches Care Home for the Elderly.

When Heather meets Izzy Strong, the home’s newest resident, she is surprised to find that they have an instant connection. And as they grow closer and Izzy begins to reveal her shocking past, Heather starts to question her own life choices…

Germany, 1927

With the Great War now a distant memory, Izzy is thrilled to be continuing her education in the beautiful city of Berlin. And when she meets the kind and handsome Garrit Shain, it seems that her happiness is complete.

But with the rise of the brutal Nazi party, ripples of unrest are once again spreading throughout Europe. And when war breaks out, the era of fragile peace comes to an end.

As a Jewish man, Garrit soon begins to fear for his life. Emboldened by her love for him, Izzy is determined to find a way to help Garrit and his family escape the horrors sweeping through Germany…

Click here to order The Divided Heart

We are delighted to announce that we have signed up a new Regency series by Graham Ley.

The Kergohan Regency Drama Series tells the story of the Wentworth family, English-French aristocrats living in Devonshire. The first book in the series, The Baron Returns, follows Justin Wentworth — a young army captain — as he makes the perilous journey to Brittany to assist a royalist uprising during the French Revolution.

The Baron Returns is available to pre-order and will be published in April 2022. The second book in the series will be released later this year.

In Graham’s words:

“I originally decided to write an historical novel in honour of my mother, Alice Chetwynd Ley, whose complete backlist (including a forgotten title, An Eligible Gentleman) has been published by Amy and the team at Sapere.

“After my first book had been accepted for publication, I found that a number of the characters were calling out for their stories to be followed through. So The Baron Returns was soon followed by a second novel, in which Arabella, the forthright heroine who had refused to let suspicions against her beloved Justin rest unchallenged, now stood up for his sister against an unscrupulous admirer.

“Both novels feature a dual and interweaved storyline, with characters in rural Brittany bound up with events in England in the turbulent period of the years just after the French revolution in 1789. And now a third novel is in preparation, which casts the intrigue into Devon and London as well as embracing love and betrayal in Brittany.

“The name of the series, The Kergohan Regency Drama Series, refers to the manor in rural Brittany that is at the centre of much of the story. The cover of The Baron Returns sets the scene magnificently, and I am delighted to have become a Sapere author.”

Click here to pre-order The Baron Returns

Congratulations to Tim Chant, whose exhilarating nautical action novel, Mutiny on the Potemkin, is published today!

Mutiny on the Potemkin is the second book in the Marcus Baxter naval thriller series: action-packed, authentic historical adventures following former Royal Navy officer Marcus Baxter during the early 1900s.

Marcus Baxter may have survived one naval battle, but his troubles are far from over.

Marcus Baxter may have survived one naval battle, but his troubles are far from over.

Despite serving with the Russian navy aboard the Yaroslovich, he is arrested by the Tsarist secret police for conspiracy and sent west on the Trans-Siberian railway to St. Petersburg. Competing factions within the secret police disrupt his journey and he finds himself in Odessa.

Odessa, though, is in the grip of revolutionary riots and Baxter finds himself trapped in the city as violence and anarchy spreads.

The crew of the Potemkin has mutinied, killing most of the officers and bringing the battleship into port.

When Baxter realises a friend is trapped in the carnage, he is determined to get onboard the battleship.

But will he make it out alive?

Click here to order Mutiny on the Potemkin

Congratulations to Linda Stratmann, whose fabulous historical mystery, Sherlock Holmes and the Explorers’ Club, is published today!

Sherlock Holmes and the Explorers’ Club is the second Victorian crime thriller in the Early Casebook of Sherlock Holmes series.

When the preserved foot of a dead man with extra toes arrives at St Bartholomew’s Medical College, the students are fascinated. However, despite this unusual feature being reported in the press, the man’s identity remains a mystery.

When the preserved foot of a dead man with extra toes arrives at St Bartholomew’s Medical College, the students are fascinated. However, despite this unusual feature being reported in the press, the man’s identity remains a mystery.

Intrigued by the puzzle, medical student Mr Stamford calls on his acquaintance Sherlock Holmes — an eccentric but brilliant young sleuth — to help him learn more about the deceased.

With only the man’s boots and a few possessions to examine, Holmes relishes the challenge. He soon finds a coded message hidden inside the man’s purse, which suggests a possible connection to criminals or spies.

Over the course of their investigations, Holmes’ and Stamford’s suspicions are strengthened when they learn of further shocking deaths. It soon becomes apparent that the men who died all belonged to the mysterious Explorers Club — and the lives of the remaining members may also be in danger.

Although the deaths look like accidents, Holmes is convinced that the men were murdered. And with conspiracy and intrigue lurking at every turn, he must now expose the secrets of the Explorers’ Club before the next member meets a grisly end…

Click here to order Sherlock Holmes and the Explorers’ Club

Congratulations to Marilyn Todd, whose gripping historical mystery, Dead Drop, is published today!

Dead Drop is the fourth book in the Julia McAllister Victorian Mystery series: thrilling British detective novels with a courageous woman sleuth at the centre.

Seeing an easy way to pay off her debts, Julia McAllister takes in three female lodgers from a travelling show.

Seeing an easy way to pay off her debts, Julia McAllister takes in three female lodgers from a travelling show.

With musical halls more popular than ever, Buffalo Buck’s Mild West is the perfect antidote to the noise and smoke belching out of the factories, and the tide of Julia’s fortune quickly turns.

Until one of the three girls is found hanging under a bridge.

Julia doesn’t believe it was suicide. Annie had been excited about the future, not depressed.

And when another body is found on the railway line, a distraught widower, inspired by Julia’s role as crime scene photographer, asks for her help as the police are refusing to give out any details.

When Julia raises the matter with Detective Inspector John Collingwood, he explains that they’re keeping the case close to their chest because the body had ligature marks, showing he’d been chained up. Their fears are that this is just the tip of a particularly nasty iceberg.

Is Annie’s death connected to the body on the railway? Can Julia work with Collingwood to solve the mystery?

Or will the secrets they uncover put their lives in grave danger…?

Congratulations to Ros Rendle, whose moving romantic saga, Resistance of Love, is published today!

Resistance of Love is set in England and France before and during World War II, and is the second book in The Strong Family Historical Saga series.

After spending ten years in Australia, Delphi Strong is on a ship back to England with her daughter, Flora.

While on board, Delphi meets Rainier, a charming vineyard owner on his way home to France. Forming an instant mutual attraction, the two share a whirlwind romance before disembarking.

Unable to forget her, Rainier crosses the channel a few months later and asks Delphi to marry him. Equally lovestruck, Delphi accepts, and she and Flora join Rainier in France.

However, their idyllic lifestyle is shattered when war breaks out and the Nazis begin to occupy the country. Forced to flee to the Free Zone in the south, the family must now pull together to resist the enemy…

Click here to order Resistance of Love

Natalie Kleinman is the author of THE RELUCTANT BRIDE and THE GIRL WITH FLAMING HAIR: glittering romantic adventures set in Regency England.

Research can come in many forms, particularly when it’s for a historical novel. One of my shelves is heaving under the weight of the books I have covering my chosen period, Regency England. And those are just the research books. Another is overflowing with novels set in that era.

Unlike our predecessors, we also have access to a wealth of information on the Internet, so much that if we allowed ourselves to follow its pull we’d never get any words of our own written, so we have to be selective. All these sources have helped in bringing to the page my latest book, The Girl With Flaming Hair.

That said, there’s nothing like seeing real artefacts. Not so easy, you might think, living as we do two hundred years after the time in question. And here’s where I feel particularly lucky. I live in London with easy access to its plethora of galleries and museums. A while ago I visited the Victoria and Albert Museum and amongst its treasures I found things that not only helped with my work in progress at the time but which also affirmed why I love this period so much. One of my characters in another book is a keen artist, and this Watercolour Box circa 1820 is a particularly treasured image.

That said, there’s nothing like seeing real artefacts. Not so easy, you might think, living as we do two hundred years after the time in question. And here’s where I feel particularly lucky. I live in London with easy access to its plethora of galleries and museums. A while ago I visited the Victoria and Albert Museum and amongst its treasures I found things that not only helped with my work in progress at the time but which also affirmed why I love this period so much. One of my characters in another book is a keen artist, and this Watercolour Box circa 1820 is a particularly treasured image.

Women’s dress changed dramatically after 1785. The rich fabrics and complicated formal shapes of the late 18th century gave way to simple, lighter fabrics that draped easily. These new gowns achieved something of the effect of the simple tunics shown on classical Greek and Roman statues and vases. This beautifully elegant creation is muslin embroidered with cotton thread.

You can see how easy it is to get carried away by research when it can be so enjoyable. I’ll leave you with one more image before I tear myself away – I have another book to write!

You can see how easy it is to get carried away by research when it can be so enjoyable. I’ll leave you with one more image before I tear myself away – I have another book to write!

This is an evening cap (1818-23) described as silk and net embroidery with silk thread; wired paper and muslin artificial flowers. I SO want one!

Click here to order The Reluctant Bride

Click here to order The Girl With Flaming Hair

We are thrilled to announce that we have signed a new Tudor saga series by Amy Licence.

Told in vibrant, colourful detail, the series follows young Thomasin Marwood as she finds her place within the turbulent court of Henry VIII.

Amy’s previous fiction has been met with critical acclaim.

In Amy’s words:

“I’m very excited to be able to publish the story of the Tudor Marwood family with Sapere Books. The saga will bring to life the English court of the 1520s, with all its intrigue and drama, through the eyes of my narrator, young Thomasin. Newly arrived from the country, she and her friends must navigate the treacherous paths of politics and love, finding their loyalties divided as Henry VIII tries to cast off his Spanish wife Catherine in favour of the young, vivacious Anne Boleyn. Temptations lurk around every corner, and secrets are waiting to be revealed, as Thomasin embarks upon a lengthy court career that will span all of Henry’s reign.”

Click here to visit Amy’s website

We are delighted to announce that we have signed up the fourth instalment of Alexandra Walsh’s captivating Marquess House Series – dual timeline conspiracy thrillers with ingenious twists on Tudor and Stuart history – as well as the next novel in her new Victorian series.

In Alexandra’s words:

“It’s wonderful to have signed with Sapere Books to continue writing about my favourite eras: Victorian and Tudor. THE MUSIC MAKERS tells the tale of another branch of the family tree established in THE WIND CHIME (the first novel in my new Victorian series). THE MUSIC MAKERS follows two timelines: one set in the Victorian era and one set in the present day. The Victorian timeline follows the life of Esme Blood, a singer and performer in the music halls and theatres of London. Adopted at birth, Esme has no desire to find her birth mother, but fate has other plans. In the present day, Eleanor Wilder is recovering from a serious illness and has returned to the family farm in Pembrokeshire to rebuild her life. Delving into Esme’s life, she uncovers a tale of love, loss and survival, all of which help her to unravel her own problems and those of the man who has unexpectedly arrived in her life.

“My other forthcoming book, THE JANE SEYMOUR CONSPIRACY, is a return to Marquess House. Although I had always intended this series to be a trilogy, when I completed it in 2020 it felt as though there was more to tell. I resisted for a while but when Perdita, Piper and Kit began interrupting my research with suggestions, I realised my trilogy was about to expand. Having always pitched it as three-book series, I was unsure how Sapere Books would feel about it continuing, but my editor, Amy Durant, said she would be delighted to return to Marquess House.

“THE JANE SEYMOUR CONSPIRACY follows Perdita and Piper as they fully embrace their lives at Marquess House. A friend of Kit’s asks for advice on a manuscript that has been in his family’s archive for generations, which seems to suggest an entirely new interpretation of the events leading up to Anne Boleyn’s execution, Jane Seymour’s marriage to Henry VIII and the death of the king’s only acknowledged illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset. In the present, danger reaches out to Perdita and Piper again as they realise their battle with the Connors family is far from over. THE JANE SEYMOUR CONSPIRACY will be released in 2022.

“THE JANE SEYMOUR CONSPIRACY follows Perdita and Piper as they fully embrace their lives at Marquess House. A friend of Kit’s asks for advice on a manuscript that has been in his family’s archive for generations, which seems to suggest an entirely new interpretation of the events leading up to Anne Boleyn’s execution, Jane Seymour’s marriage to Henry VIII and the death of the king’s only acknowledged illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset. In the present, danger reaches out to Perdita and Piper again as they realise their battle with the Connors family is far from over. THE JANE SEYMOUR CONSPIRACY will be released in 2022.

“Being part of the Sapere Books family is one of the best things about being published; Amy, Caoimhe, Richard, Natalie, Matilda and Helen make everyone feel so welcome and are a dynamic and forward-thinking team. My books could not be in safer hands. The weekly Zoom meet-ups with the other authors are fascinating, funny, inspiring and often educational! It’s a great feeling to be part of such a talented group of writers and publishers who are always willing to help or offer advice.”

Click here to find out more about The Marquess House Series

Click here to pre-order THE WIND CHIME

Following the publication of David Field’s absorbing Esther & Jack Enright Mysteries, Tudor Saga Series and Carlyle & West Victorian Mysteries, we are delighted to have signed up his new Medieval Saga Series.

In David’s words:

“I consider myself blessed to have found Sapere Books, who not only share my enthusiasm for historical novels, but also provide the most generous author royalties in the business, and never lose sight of the fact that their many authors have invested a massive amount of emotional energy into creating, nurturing, and revealing their characters.

“It’s therefore with great optimism and a sense of purpose that I’ve embarked on my latest venture with them — the Medieval Saga Series, a set of seven novels that follow the fortunes of the same family from immediately prior to the Battle of Hastings all the way through to the death of Simon de Montfort in the Battle of Evesham in 1265.

“The first in the series — THE CONQUEST — introduces the Riveracres, a Saxon family living on the Sussex coast whose tiny village is directly in the path of Duke William of Normandy’s invasion army, and the Astenmedes, the local Thegn’s brood whose traditional privileged status is about to be shattered. Amidst the turmoil, two brave men, Will Riveracre and Selwyn Astenmede, form an unlikely partnership as they stand against both Duke William and Harald Hardrada’s invading Viking force to the north.”

Click here to find out more about the Esther & Jack Enright Mysteries

Click here to find out more about the Tudor Saga Series

Click here to find out more about the Carlyle & West Victorian Mysteries

Natalie Kleinman is the author of The Reluctant Bride, a glittering Regency romance with a strong-minded heroine at its heart.

I spent the first few years of my career writing contemporary romantic fiction, firstly short stories and then novels, until the burning desire I’d had for so long pushed itself to the forefront. I wanted to write a historical novel set in England’s glorious Regency period. Maybe I couldn’t, but I had to try. I’d previously looked upon it as a presumption on my part even to consider it, bearing in mind my love for the works of Georgette Heyer and Jane Austen. But I wasn’t trying to emulate them. I was trying to make my own contribution the genre that had given me so many hours of joy over decades. And so my first Regency novel, The Reluctant Bride, was born, to be followed by another, and then another. They’ll be coming soon, so watch this space.

Charlotte Willoughby — the heroine of The Reluctant Bride — is a young woman of her time. Born into the aristocracy, she is as much tethered by her status as privileged. When she is forced by her father to marry the Earl of Cranleigh, purely to satisfy his own interests, she has no choice but to comply. Six weeks later, fate takes a hand when her husband is killed in a riding accident. Free of a tyrannical parent and a loveless marriage, Charlotte begins to enjoy her newly found independence. Gresham, the earl’s cousin, undertakes to guard her from fortune hunters and, while she finds him arrogant and aloof, she cannot deny the security his protection affords her, particularly with regard to the unwelcome attentions of Lord Roxburgh. Acutely aware of the tension between the two men, Charlotte learns they have a shared history, the animosity of which still lies between them. With the coldness of one and the over-heatedness of the other, will she be able to find her own path to happiness?

Writing The Reluctant Bride, I settled into a deeply satisfying place where I was able to weave a tale while indulging in my love of the setting. I could see the magnificent houses and the glorious balls, but beneath all ran the story of a young woman, struggling with adversity, triumphing over it and finding her own way. I hope you enjoy it.

Click here to pre-order The Reluctant Bride

Click here to subscribe to Natalie’s newsletter

Set in seventeenth-century Leiden, The Netherlands, Graham Brack’s funny and immersive Master Mercurius Mysteries follow Mercurius — a witty university lecturer-cum-sleuth.

The first four books in the Master Mercurius series are published, and we are delighted to have signed up the next instalment: THE VANISHING CHILDREN.

In Graham’s words:

“I’ve been delighted with the response from readers to the Master Mercurius Mysteries. It’s wonderful to read good reviews, not only for myself, but also for Sapere Books, who always had faith in the stories. Being part of the Sapere family is very encouraging to any author; we enjoy our colleagues’ successes. I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else.

“The fifth book sees Mercurius sent to Amsterdam which — even in 1684 — was not a place where a minister who has led a sheltered life as he has would feel comfortable. On top of that, he has been sent to bully the city authorities into handing over their taxes in full. However, while he is there, he is approached by a local merchant who tells him that three children have gone missing, and their families have been fobbed off by Amsterdam’s powers that be.

“So begins an inquiry that makes Mercurius question his own faith as well as his suitability for the task he has been given…”

Click here to order DEATH IN DELFT

Click here to find out more about the Master Mercurius Mysteries