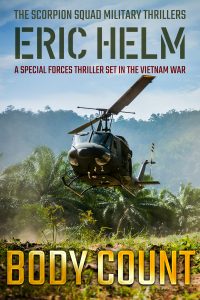

The Scorpion Squad Military Thrillers follow an American Battalion fighting in the Vietnam War. Below, Kevin D. Randle (Lt. Col. USAR) — one of the authors behind the pseudonym Eric Helm — reflects on the real-life experiences that provided the inspiration for the series.

I graduated high school the day before my 18th birthday in June 1967. In July, I was on a bus headed to Fort Polk, Louisiana, for basic  infantry training and in October, I was assigned to Fort Wolters, Texas, for my AIT, advanced individual training, which was as a helicopter pilot. From there I was sent to Fort Rucker, Alabama, to complete that training. In August 1968, as a 19-year-old teenager, I was appointed a warrant officer and then graduated from flight school as a helicopter pilot.

infantry training and in October, I was assigned to Fort Wolters, Texas, for my AIT, advanced individual training, which was as a helicopter pilot. From there I was sent to Fort Rucker, Alabama, to complete that training. In August 1968, as a 19-year-old teenager, I was appointed a warrant officer and then graduated from flight school as a helicopter pilot.

On September 23, 1968, I arrived in South Vietnam. We landed at Ton Son Nhut and were herded aboard buses that had no air conditioning. We all were covered with sweat within minutes of leaving the aircraft. The bus had screens over the open windows, but the pattern was something like an inch square. It wouldn’t keep out the insects. Someone said it was to keep out the grenades, and someone else said, “Yeah. Now they tie fishhooks to them.”

From Saigon we drove to Bien Hoa, Long Binh complex and the 90th Replacement Battalion. From there, a day or two later, I, with three other warrant officers, was assigned to the 116th Assault Helicopter Company at Cu Chi.

Kevin Randle after a day of flying combat assault missions in Vietnam.

During that first week, I flew rarely. There was an orientation flight to show me the local area. There was a check ride to ensure that I knew what to do if the engine quit, and to demonstrate my other skills. When that was completed, I was assigned to a flight, and then began flying combat assault missions. That meant that we picked up soldiers in one place, took them to another and landed. While many of those missions were without incident, some of them were more than a little exciting. Nothing beats sitting in a pick-up zone to evacuate soldiers while the enemy pumps small arms fire into the flight. You’re sitting in a plexiglass encased cockpit, easily visible to the enemy and have no recourse but to sit there as the windshields break and the instrument panel disintegrates.

One of the first night missions I flew, as what was known as a peter pilot, meaning that I was the co-pilot, was into an PZ we knew was going to be hot. The soldiers were taking fire and we were going to extract them. There were tracers flying all over the place. Red ones from our weapons and green and white ones from the enemy. They dropped a few mortars on us as well, which erupted into a shower of sparks and had that been just a little more colourful, it would have looked like fireworks.

Flying formation on the way to a combat assault.

Everyone took some hits, but most of the damage was superficial. One of the aircraft, if I remember correctly, was left in the PZ. The engine had been hit and failed. The crew was picked up by another aircraft, which means that they abandoned the aircraft and ran to one of the others. The gunships, which had been working over the tree lines and enemy positions, took it out with rockets, setting it on fire to prevent the enemy from getting anything of value from it.

We were on the ground for thirty seconds to one minute as the soldiers scrambled onto the helicopters. Our door gunners and crew chiefs used their M-60 machines in an attempt to suppress the enemy fire. They aimed at the muzzle flashes of the enemy weapons.

That was the last flight that night. Once we had the soldiers out, I suspect the Air Force might have dropped some ordnance on the enemy positions, or the artillery might have dropped a few rounds on them. I really don’t know. Once we dropped off the soldiers, we were released and returned to Cu Chi so that maintenance could patch up the aircraft.

We are delighted to announce that we have signed a new Tudor mystery series by C P Giuliani.

The Tom Walsingham Mysteries follow a young sleuth as he becomes embroiled in the shady world of espionage. The first instalment will be published in 2021.

In Giuliani’s words:

“Signing with Sapere Books for my first murder mystery series has been truly wonderful!

“Book 1, A Road to Murder, is set in 1581 between England and France, and follows a young diplomatic courier’s efforts to untangle a murder that could have wider, political implications. With France constantly teetering on the brink of religious unrest, and Queen Elizabeth toying with the idea of marrying the French king’s Catholic heir, even the death of a glove-maker can hide sinister machinations. And my hero, Tom Walsingham — a relation to Queen Elizabeth’s powerful spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham — knows better than most just what could be at stake…

“This is going to be my first publication in the UK, and Amy and the whole team at Sapere Books are being incredibly supportive, friendly and very competent — and they have gathered together a very welcoming author community. A lovely experience through and through.”

Sapere Books are proud to sponsor the Crime Writers’ Association’s Historical Dagger Award, which is for the best historical crime novel set in any period at least 50 years prior to the year in which the prize is presented.

The 2020 shortlist featured eccentric doctors, notorious gangsters, stolen diamonds and much more.

On Thursday night, the fabulous Abir Mukherjee was announced as this year’s winner at the Crime Writers’ Association’s digital awards ceremony. His winning novel, Death in the East, is the fourth instalment in his Wyndham & Banerjee Mysteries Series.

Set in 1920s India, Death in the East follows the continuing adventures of dynamic duo Captain Sam Wyndham and Sergeant Surrender-not Banerjee. Wyndham is haunted by an old case from his early days as a young constable, when his old flame Bessie Drummond was found beaten to death in her own room. Arriving at the ashram of a sainted monk – where he hopes to overcome his opium addiction – Wyndham finds a shadowy figure from his past, a man he believed was long dead. Certain that the man is out for revenge, Wyndham once again calls on Sergeant Banerjee for help. Together, they prepare to take on a sadistic and slippery killer…

We would like to send a huge congratulations to Abir, and to all of the wonderful authors who were longlisted and shortlisted this year.

Stephen Taylor is the author of A CANOPY OF STARS, a thrilling historical 19th century saga stretching from the legal courts of Georgian London to the Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt.

When I start to write a novel, the first thing I always do is open a document that I call ‘Conceptualising’. I put down my initial thoughts, sketch out a skeleton storyline. Then I start researching and populate this document with historical facts and ideas that I can use.

When I came to write A CANOPY OF STARS, my first port of call was a website — Punishment at the Old Bailey: Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Here I could view actual cases going back hundreds of years. I came across the trial of Peter Shalley (REF: T17900113-17) that took place in 1790. Shalley was a German immigrant who was accused of the theft of half a sheep’s carcass worth just 40 shillings. His story, through an interpreter, was that he was offered a shilling to carry the carcass to Oxford Road from a field outside London. When he said he didn’t know where Oxford Road was, the man said: ‘Don’t worry, I’ll walk behind you and each time you come to a junction, look behind you, and I’ll point which way to go.’ When he got to Oxford Road, the Watchman challenged him, and the other man ran away. To me, this was a reasonable defence — he had been duped.

But the system was stacked against him, for while he was an educated man, he was a Jewish immigrant and spoke little English; he was seen as just another piece of London’s low life to be dispatched by the hangman with little ceremony and no one to mourn him. Even the valuation of the sheep at exactly 40 shillings made it a felony (not a misdemeanour) and therefore punishable by death.

I found this disturbing; it may have been over two hundred years ago, but I was stung by the injustice of the case. I was upset; the wrong done to this man was so plain to see and became like a nagging toothache. So I resolved to restructure A CANOPY OF STARS; it would still be a Georgian courtroom drama, but — through the character David Neander — I would also write Peter’s own story as I saw it. Images danced in my mind; what sort of man was this Peter? Why had he left his native Germany; why had he come to England?

In England, this was a time of the enlightenment; there was a clamour for reform. Power, however, lay in the hands of the aristocratic landowners who viewed reform as a threat. In the German states, this was a time of nationalism, a distrust of all things un-German. This is the backdrop to David’s story. How did he navigate his way through it?

Click here to order A CANOPY OF STARS

Marilyn Todd’s witty and atmospheric Julia McAllister Victorian Mysteries follow a courageous female photographer-cum-sleuth as she investigates London’s shadiest characters.

The first two books in the series — SNAP SHOT and CAST IRON — are already published, and we are delighted to have signed up the next two instalments.

In Marilyn’s words:

“I’m thrilled to be continuing Julia’s story, and quite frankly, having this series in the hands of a dynamic publishing team like Sapere is the icing on the cake!

“The third instalment, BAD BLOOD, sees Julia tasked with photographing the scene of a factory owner’s murder. A man who treated his workers like dirt, and his wife even worse. It’s not so much a question of who’d want him dead — more who wouldn’t. But eight years earlier, his son was abducted, and Julia soon realises that the kidnap and murder are connected. The trouble is, knowing who’s responsible is one thing, proving it is quite another. Especially when the killer knows she’s on to them.

“This is followed by DEAD DROP. Music halls were a popular antidote to the noise and smoke belching out of the Industrial Revolution, but the lives of the entertainers were gruelling. When a young showgirl is found hanged, Julia doesn’t believe it was suicide. Too late, she discovers that the truth hurts, but secrets kill, putting her own life on the line…”

Click here to find out more about the Julia McAllister Victorian Mysteries

Elizabeth Bailey’s Regency-era Lady Fan Mysteries follow Ottilia, a courageous woman sleuth faced with gruesome deaths, buried scandals, witch hunts and more.

The first six books in the series are already published, and we are delighted to have signed up the seventh, THE DAGGER DANCE.

In Elizabeth’s words:

“In THE DAGGER DANCE, Lady Fan is off to rescue a Barbadian slave girl accused of murder. I’ve been wanting to bring this story to light, since Ottilia long ago guessed her steward Hemp had a secret heartache for a lost love. Bristol was at that time a major port for shipping traders doing the rounds from Africa to England and the West Indies. The research was almost as engaging as writing the book.

“With this seventh adventure, I count myself a very lucky member of the Sapere Books author family. Sapere has done wonders for Lady Fan, and it’s a joy to be with such a supportive and encouraging publisher where the author’s contribution is so much valued and validated.”

Click here to order the first Lady Fan Mystery, THE GILDED SHROUD

Click here to find out more about the Lady Fan Mysteries

J C Briggs’ gripping Charles Dickens Investigations follow the famous writer-turned-detective as he dives into the seedy underbelly of Victorian London.

The first six books in the series have been published, and we are thrilled to announce that we have signed up the next two instalments.

In J C Briggs’ words:

“I am thrilled that Sapere Books are to publish two new cases featuring Charles Dickens and Superintendent Jones. Number seven in the series is THE HAWKE SAPPHIRES, which begins at Hawke Court, an almost derelict mansion where Sir Gerald Hawke is dying. His two wives and his only son are dead. His heir is a clergyman, Meredith Case, for whom Hawke has one last command. Hawke has commanded all his vicious life and expects to be obeyed. Meredith Case must ‘find Sapphire Hawke’, who vanished over twenty years ago.

“A chance meeting with Charles Dickens sends Case to the north of England. Meanwhile, Dickens and Superintendent Jones of Bow Street are investigating the death of a young man who was found on the steps of a bookshop.

“Charles Dickens begins to suspect that the two cases are connected. He and the young detective, Scrap, experience a frightening night at Hawke Court.

“Book eight in the series is THE CHINESE PUZZLE. On the first day of The Great Exhibition in May 1851, a Chinese man bowed before Queen Victoria. It was assumed that he was a representative of the Celestial Empire. He wasn’t. It was reported in the newspapers of the day.

“In THE CHINESE PUZZLE, behind the scenes the Home Secretary is furious at the breach of security. There have been attempts on the Queen’s life before.

“And also concerning for the government, a wealthy banker and former opium merchant of Canton vanishes on the first day of the Exhibition. The Prime Minister, Lord John Russell, appoints Superintendent Jones to carry out a most secret investigation. The case may involve high-powered bankers and politicians. Jones cannot afford to get it wrong. Only Charles Dickens can help him find his way about the houses of some very important people. There is danger from high and low when the case takes them to the East End opium trade and some very dangerous criminals.

“It really is great to work with Sapere Books again and to know that they have faith in my series. They are a wonderfully supportive publisher to all the writers in the Sapere family.”

Click here to order THE MURDER OF PATIENCE BROOKE

Click here to find out more about the Charles Dickens Investigations

Following the publication of Graham Brack’s darkly funny Josef Slonský Investigations – atmospheric police procedurals set in Prague – Sapere Books recently started publishing his Master Mercurius Mysteries: 17th century crime thrillers set in Leiden, The Netherlands. Taking centre stage is Mercurius – a witty university lecturer-cum-sleuth.

The first three books in the Master Mercurius series are published or available to pre-order, and we are delighted to have signed up the next instalment: THE NOOSE’S SHADOW. The fourth book sees Mercurius free from the demands of the Stadhouder – William I of Orange – for once as he is asked for help by a poor young woman whose husband faces execution for a murder he swears he did not commit. How can Mercurius refuse?

Graham says, “I was already part of the Sapere family after Amy signed me to write six Slonský novels, so I knew Sapere Books was the right place for my Dutch series too – and Slonský will be back! We’re a very supportive bunch of writers who enjoy each other’s successes, and the Sapere team is simply excellent. I couldn’t imagine going anywhere else with the Mercurius books.”

Amy says, “I have already worked with Graham on eight published books since we launched in March 2018, and I am thrilled to have signed his next book. I hope there will be many more! Fans of his previous series are already calling for a return of Slonský, and they seem equally smitten with Master Mercurius. I thoroughly enjoy reading Graham’s books and look forward to editing many more in the series.”

Click here to order DEATH IN DELFT

Click here to find out more about the Master Mercurius Mysteries

Chapter One

The taxi swung out of the avenue and I got my first view of Grovestock House, its blindingly white stucco frontage gleaming in the autumn sunlight. The drive curved gently round a neatly manicured lawn and our wheels crunched on the gravel as we pulled up outside the front door.

As I stood outside waiting for the doorbell to be answered, I wasn’t sure if there would be anything challenging in this case.

‘Just go through the motions,’ Dyer had said to me. ‘There needs to be the appearance of a complete investigation, but we already know what happened. And remember, it’s not me wanting another look at it, it’s the Chief Constable. He’s getting pressure from the press, who think we should have investigated the deaths more thoroughly. They’re suggesting the case wouldn’t have been tied up quite so quickly if the family wasn’t so well connected.’

Briefly, we went through the file together. I recognised the outlines of the case from the newspaper coverage. “Warwickshire House of Death” had screamed one headline, followed by every grim detail of the tragedy. Lady Isabelle Barleigh had killed her wheelchair-bound son with a shotgun before turning the gun on herself. This had been quickly followed by the suicide of the young man’s fiancée. What made the whole affair more chilling was that the couple were to have been married two days later. Instead, they were now sharing a graveyard. I’d felt ill reading the article but, on the face of it, the facts had looked clear. Nevertheless, I was hardly surprised when questions started to be asked about why the whole matter was despatched so quickly. The deaths had only occurred a few days earlier and, somehow, strings had been pulled to convene a quick inquest and then a funeral to replace the wedding celebrations.

Now I was wishing I’d argued more against being assigned to this one, especially as Dyer had taken me off the Jewish beatings investigation and passed it to that idiot Terry Gleeson. If what happened at Grovestock House was as clear-cut as the preliminary work suggested then why give it to me? I’d told him that there were plenty of other good coppers around who’d adequately tie up the loose ends. I think Dyer knew the Bishop and Stack case had given me a good deal of pain and he was trying to do me a favour. Or perhaps his instincts told him that the initial enquiry had been a bit cursory and, perhaps, unreliable.

Anyway, I hadn’t resisted much so I’d left, briefly calling in to my station in Kenilworth, then home to collect a few things, arriving at Grovestock House before lunch. On the way I’d re-read the file and acquainted myself with the facts as they’d been recorded so far. It was unfortunate that a few days had passed and allowed the trail to cool but it couldn’t be avoided in the circumstances.

The local constable, Sawyer, had been pretty thorough in his approach. He’d been telephoned about the deaths around midday, cycled over as soon as he could, arriving an hour later. By then, the body of the fiancée had been discovered; she had shot herself with the dead man’s revolver. First thing he did was make sure the gates were guarded. Nothing to be done for Tom Barleigh, his mother or girlfriend, so he set about photographing the scenes and interviewing witnesses, several of whom told Sawyer that Lady Isabelle had been increasingly set against the marriage, though none knew why. He’d written his notes up swiftly and gone through them with Gleeson, who hadn’t bothered to interview anyone himself. Just like him, idle bugger.

The local doctor decided there was no need for a post-mortem and Sawyer presented his evidence to the inquest, which made the same conclusions he had. It was starting to bother me that everything had been despatched so quickly, so neatly.

I had done my research on the family prior to my visit. Grovestock House had been built sometime in the middle of the eighteenth century when Thomas Barleigh had wanted a new home to reflect his recently acquired status as a Privy Councillor to King George III. He’d been appointed following his generous support to the monarch in a series of conflicts with France, particularly in the Americas. Thomas was no soldier though, he was one of the new breed of industrialists, building up a fortune manufacturing muskets and pistols. Items put to good use by George’s army in its attempts to suppress uprisings across the empire.

Thomas’s grandson, having become a regular drinking partner to the Prince Regent, was raised to a baronetcy when the prince ascended the throne in the early eighteen hundreds and the house had been refurbished and extended to celebrate. Shifts in political allegiance over the next two centuries meant Sir Arthur Barleigh, the present incumbent, no longer had the power and influence his ancestors enjoyed. Nevertheless, the family was still important in the social merry-go-round of the county, hence the newspapers’ interest and the Chief Constable’s newly-found desire to make sure the job was done thoroughly.

A man in his late forties swung open the door. He wore a dark jacket and pin-stripe trousers, and his hair was greying at the temples. He gave off the unmistakeable smell of brilliantine as he looked at me enquiringly over the rim of his glasses. He was beyond question a butler and I remembered from Sawyer’s report that his name was Jervis.

‘Inspector James Given, Warwickshire Constabulary. I believe you’ve been expecting me.’

‘We have, sir. Sir Arthur asked me to prepare a room for you so I’ll take you up if you’ll follow me.’

‘There’ll be no need, thank you, Mr Jervis, I won’t be staying here tonight. I’ve already booked a room in the village. However, you can look after my overnight bag for now if it’s not too much trouble.’

He took it and asked if there was anything else I needed. I told him I’d like to have a look at where the deaths took place.

‘Very good, sir, would you like me to accompany you?’

‘No thank you, that won’t be necessary, just show me where Lady Isabelle and her son died.’

He pointed to the left of the house. ‘The shootings took place down there, sir, on the side lawn.’

I let the butler go about his business, instructing him to tell everyone in the house I’d arrived and would be conducting interviews later in the day. I didn’t think for a moment I’d get through many but it would do no harm to put them under a little pressure.

Before heading to the side of the house I turned on the step and surveyed the grounds. It wasn’t a grand estate by any means and I suspected it had once been much grander. Perhaps a profligate ancestor had squandered too much of the family fortune on high living. It still remained a couple of hundred acres at least, judging by the distance from the gate to the main house. A lawn, directly in front of the main door, was circled by the drive and bordered by several dozen rose bushes, whose scent would have been breath-taking in the height of summer. At its centre stood a magnificent cedar, fully thirty feet across and towering well above the roof top. The whole garden was walled or hedged on the two sides, with openings to further gardens, woods or fields beyond. The entire landscape sloped down to a lake sculpted into the fields below.

When I turned again and stepped back, I was able to take in the full grandeur of the house. There were two enormous bays rising to the roof and there were roughly twenty windows, all in the Georgian style. Ruefully, I compared this with the single window on each floor of my own little cottage in Kenilworth. The gravel crunched beneath my feet as I walked to the side lawn and through the gate. High walls and hedges surrounded the area and it was obvious that whatever had taken place here wouldn’t have been seen from anywhere in front of the building. Not unless someone was close enough to the gate. I noted there was no other access, or exit, apart from a side door into the house. The side walls were of much plainer red-brick and of a much earlier period, the grand frontage being merely a façade. I wondered what else in this case might be not what it seemed on the surface.

‘Good afternoon, constable.’ I looked at my notes. ‘Sawyer, isn’t it?’

‘Yes sir, John Sawyer.’

‘I’ve had a chance to have a look at your report but there are a few things I need to go over with you, to get them clear. Well done with the photographs, by the way, a very thorough touch.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

He’d joined me at Grovestock a few minutes after my inspection of the front gardens. He was tall even for a copper, towering over me when I stood to shake his hand. His blond hair and fresh features, accompanied by the flushed cheeks when I praised his work, gave the impression of an overgrown schoolboy in a policeman’s uniform.

‘I had my Brownie with me, sir; I tend to put it in my saddlebag when I’m out in case I see anything interesting to photograph on the way. There’s not usually much use for it in my work round here, though. Lost cats, neighbour disputes, that kind of thing. I’m lucky enough to have a darkroom at home so was able to develop them myself as well.’

Sawyer’s boyish enthusiasm was naive, but clearly he was smart and not afraid of using his own initiative. I was certain it would have been the first murder he’d looked at so he’d done well to keep calm and record everything as fully as he had.

‘Why did you conclude Isabelle Barleigh had shot Tom and then herself?’

‘Well, it all looked very obvious on the day, sir. The two of them were lying on the ground with the weapon between them. He’d been shot in the chest from close range, toppling him out of his wheelchair, and she’d shot herself under the chin, really the only way she could have done it with a shotgun.’ Sawyer turned green as he remembered. ‘Also, people from the house and the estate were there in minutes, so it seemed unlikely that anyone could have carried out a murder then disappeared down the road without being noticed.’

‘Not likely, or not possible?’

He now hung his head slightly at the thought he might have missed something.

‘I suppose it might barely have been possible, sir, for someone who knew the place well enough.’

I asked him if there was anything else at the scene, anything at all which might suggest a different set of circumstances.

‘Nothing really, sir. The only slightly odd thing was that Lady Isabelle had a scrap of paper clutched in her left hand.’

‘Paper?’

‘It appeared to be a bit of a letter, judging by the partial address in one corner. It turned out to be that of Miss Bamford’s father, Gerald Bamford. I searched the garden thoroughly but didn’t find any more of it and presumed the scrap was all she had.’

‘And what about Jenny Bamford? You concluded she’d committed suicide as well. Did she leave a note?’

‘There was no note, at least none that I found. When I was let into Tom’s room by Jervis, Miss Bamford was lying on the bed with the revolver on the floor below her hand. It seems that the gun belonged to Tom Barleigh and everyone knew he kept it in a drawer in his bedroom. She had a single bullet hole to the side of her head and the pillow was covered with blood, so it was clear she’d died where she lay.’

He looked queasy again so I let him settle before continuing.

‘Did you interview everyone when you arrived?’

‘I took statements from everyone there. You’ll know from the file that Billy Sharp and Tom Barleigh’s nurse, Trudi Collinge, disappeared before I could interview them. I would have liked to speak to Jenny’s family as well, to see if she’d been unhappy and so on.’

‘But you didn’t manage it?’

‘No, it wasn’t possible. Parents are divorced, she’s in Australia and remarried. We sent a telegram to the local police so they could let her know her daughter was dead. Her father showed up briefly at the funeral but then left part way through before I could speak to him. I asked one of the other lads to call round to see him but apparently the house looks like it’s been empty for a few days.’

‘What about Sir Arthur? Did you get a full statement out of him?’

‘That wasn’t easy, sir, but I did get something. I was told by the butler that Sir Arthur had some urgent business which he needed to attend to and it would be really helpful if I could interview one or two of the others first. It made no real difference to me so I just got on with seeing everyone else that I could. When I’d finished, Jervis came to fetch me to go to Sir Arthur’s study. He seemed a bit surprised to see me still there but did agree to be interviewed. Apart from telling me where he was when each of the shootings happened he wasn’t able to add anything to what everyone else had said.’

‘Did he suggest any reason why his wife might have done such a thing?’

‘He said he was at a complete loss about it. To be honest, he seemed … overcome, if you understand me. Like he didn’t really know what was happening. I thought I’d best leave it alone until I was told to do otherwise by someone more senior. I did telephone next day in case he was feeling any better but was told he’d been given sedatives and was sleeping.’

‘Tell me about him. How is it that he’s “Sir” Arthur?’

‘He’s a baronet and inherited the title. It’s come down through about eight generations until he took it over when his father died at the end of the Great War. That was about the same time he married Lady Isabelle.’

‘“Lady” Isabelle? She was a proper toff then, was she?’

‘No, I don’t think so. I’d be fairly sure she picked up the title from him. I don’t know much about her but I’ve an idea she was just a local girl who got lucky.’ Sawyer then came up with a question he must have been dying to ask since we met. ‘Excuse me, Inspector, and I know it’s perhaps none of my business, but why has it taken so long for someone to follow up the case? I mean, I know Inspector Gleeson went through the file but he didn’t even come down to the house, just met me at the station. Said there was no need. But now you’ve turned up.’

‘You’re right, it would have been much better if I’d have been able to make it straight away but I wasn’t available. On the day I was still tied up with the Peter Bishop hanging.’

‘I read about that case. Didn’t they kick a Jewish butcher to death in Birmingham?’

‘They did. Bishop and Stack scarpered but I got lucky when they were heard bragging about it in a pub. They were both members of a Blackshirt gang, followers of that idiot Mosley, and had been planning the attack for weeks. Anyway, by the time it was over, you and Inspector Gleeson had finished the investigation.’

I told him Gleeson had forwarded the file to the Chief Constable with a recommendation for no further action.

‘If you hadn’t made such a convincing case for a murder and two suicides it might have been chased up sooner.’

‘I’m sorry, sir, it all seemed so clear cut.’

‘Don’t worry about it, you did a good job. I can think of half a dozen officers, with much more experience than you, who would have come to the same conclusion. It was only after the inquest, when the big boss started getting pressure from the newspapers, that he asked Superintendent Dyer to have another look.’

‘And you think there’s more to the case than meets the eye, sir?’

‘I don’t know, but it’s all a bit too neat and tidy for my liking. Let’s just sniff around a bit longer and see what turns up. If it’s nothing more than me being overly cautious, then you’ll gain more respect from your colleagues and I’ll have had a nice day or two in the Warwickshire countryside.’

Sawyer filled me in on the other interviews he’d carried out with the household staff and the gardeners. No-one had witnessed anything and all except the butler were able to account for where they were when the shootings happened. Sawyer had also spoken to a friend of Tom’s, Alan Haleson, who was staying at Grovestock House and would have been his best man at the forthcoming wedding. Haleson had reported his version of the events but was on his own when each of the shootings took place.

‘So what would you like me to do now, Inspector?’

‘It’s imperative we find the young gardener, Tom’s nurse, and Jenny Bamford’s father. And I’ve to get a full interview with Sir Arthur. You follow up the first three as best you can. I’m going to finish reading the file and then go back to the bereaved husband and a few of his staff. Let’s see how we get on and we’ll meet up again tomorrow.’

I found Jervis in his pantry, a small room between the kitchen and main part of the house. This was the nerve centre of his fiefdom. There was all the paraphernalia associated with ensuring the life of his master was well run and comfortable: the wine coolers, ice buckets, silver trays, cutlery boxes and so on. The room also contained a small table and two chairs; an old one seemingly from the kitchen, and a slightly more welcoming one placed in the corner. Jervis had an open ledger on the table when I popped my head round the door. A number of others were neatly stacked on the shelf above him.

‘You look busy, Mr Jervis.’

‘Not really, Inspector, just catching up on some paperwork.’ He smiled sorrowfully as he got up to beckon me inside. ‘Much less to do now with fewer people in the house. We were expecting this to be such a happy time. How can I help you?’

The man looked upset and seemed to be putting on a brave face for the sake of the other servants. He must have felt the tragedy as heavily as everyone else.

‘I need to see Sir Arthur. Could you go up and tell him I’m here and want to interview him?’

‘I’m afraid I can’t, sir, he’s not here.’

‘Not here? A moment ago you said he was in his room most of the time. I thought I asked you to tell everyone I’d like to see them today.’

‘I’m sorry, sir, I should have said when you arrived. He decided this morning he needed to get out of the house so left quite early for a ride.’

‘Does he often do this?’

‘Before all of this happened he’d go out several times a week and could be away for hours. On more than one occasion he’d travel as far as Banbury and back in the day; a good three hours’ journey in each direction. I believe he thought you wouldn’t be here until the evening. I couldn’t say when he’ll come home but I’ll let him know you want to see him if you’re still here. He’s said we need to give the police as much assistance as we can and I should put the house at your disposal if you need somewhere to stay or work.’

I was annoyed at Sir Arthur’s absence but all I could do was interview the butler and hope his employer would return soon. I thanked Jervis for the offer of a room to work in, took a seat and checked some of the details from the file with him.

‘So where were you at the time of the first shootings, Mr Jervis?’

‘It’s as I told the Constable, sir. I’d just entered the lift upstairs and pressed the button to come down. I wouldn’t normally use it, of course; the servants aren’t really allowed. We’re supposed to use the side stairs, but I was bringing down a large basket of bed linen that needed to be aired for the guests due to arrive.’

‘Surely that isn’t your job?’

‘It’s usually one of the maid’s jobs to fetch the linen but there was so much it needed someone stronger. I thought the first bang was something to do with the lift machinery starting up. Then, when I’d travelled a few more feet, I heard the second bang and was certain it was a gunshot fairly close by, much closer to the house than would be usual. I got out as soon as the lift arrived on the ground floor then saw Miss Parry at the bottom of the stairs, about to run out of the front door.’

There was a silence.

‘And who is Miss Parry?’

I think I knew the answer before he gave it. It would be too much of a coincidence for it not to be her.

‘Miss Elizabeth Parry is the housekeeper, Inspector.’

I hadn’t expected to hear her name ever again. It made my stomach churn and my head spin.

‘So what did you do?’

‘I knew something must be wrong so I joined her. Mr Haleson, Mr Barleigh’s friend, also appeared at that point and came with us. I wasn’t sure which direction to go but she said it was on the side lawn so we went that way. I shouted for her to stay behind me in case there was still any danger.’

‘That was very brave of you, Mr Jervis.’

‘I don’t know about brave, sir; I was doing my duty.’

I went on to question him about what he’d seen when he arrived at the side lawn and he repeated what he’d told Sawyer. He also confirmed he’d gone inside to find Sir Arthur straight after the bodies were discovered. He had asked Elizabeth Parry to tell the rest of the staff what had happened.

‘You let Miss Bamford into the house when she returned?’

‘I did.’

‘And you told her what had happened?’

‘Oh no, Inspector. I was under strict instructions from Sir Arthur not to say anything, that I should simply inform her he wanted to see her upstairs in his room.’

Jenny left him in the hallway and climbed the main stairs to the upper landing. Shortly afterwards he was making his way to the kitchen to join the other staff when he heard a shot from upstairs. He ran back through the house and up the central staircase then searched from room to room to try to find where the shot had been fired. He arrived at Tom Barleigh’s room last of all and saw Sir Arthur and Alan Haleson standing over Jenny Bamford. A revolver was on the floor beside the bed.

His voice caught in his throat when he recalled seeing the dead young woman, though his face gave nothing away. I couldn’t help wondering if he was perhaps fonder of her than of the others. There was nothing else he could tell me so I asked him to contact me straight away if he thought of anything important he’d missed. I didn’t really expect he would. Jervis had a butler’s loyalty so family secrets would remain secret.

Sir Arthur still hadn’t returned when I’d finished with the butler. I decided to move on to the maid who had witnessed the first two deaths on the side lawn. I asked for her to be sent to the room which had now been put at my disposal, the “morning room”. I’d spent several years at sea, often with four to a cabin, and it amused me to think the aristocracy have special rooms they only utilise at particular times of the day. I even think my own little cottage is spacious, having the luxury of an extra bedroom for me to use as an office.

Marion Clark stood before me, looking nervous, and confirmed she was upper housemaid to Sir Arthur and Lady Isabelle Barleigh. She’d been in their employment for about two years. There was something about the girl’s face that hinted at a touch of stupidity and though she was twenty years old or thereabouts, she looked much younger.

‘You were interviewed by Constable Sawyer on Tuesday, weren’t you, Marion?’

‘Yes sir, I was, sir.’

‘Well, I’m a detective and an Inspector, so much more senior than he is and there can be no lies from you. Do you understand me, Marion?’

If the girl had been nervous before, she now looked like she’d faint away any moment, her eyes darting this way and that, and her hands wringing her apron front.

‘I understand, sir. I wouldn’t lie.’

I told her to take a seat.

‘You’ve known the family for a good while now, so what do you make of them?’

She appeared to struggle for words.

‘They’ve always treated me well, sir.’

‘I wasn’t asking how they treat you, Marion. Were Sir Arthur and Lady Isabelle a happy couple?’

‘That wouldn’t be for me to say, Inspector Given, I’m not one for telling tales.’

‘But that’s exactly what I want you to do, Marion. In fact, I’m actually expecting you to tell tales. We have three deaths here and I dearly want to get to the truth of what happened. But we’ll perhaps come back to what you think of the family a little later. For now you can tell me what you saw on Tuesday.’

‘Tuesday? Well, sir, Tuesday is my day for cleaning Mr Tom’s room. His nurse, Miss Collinge, sees to it most days but once or twice a week the other staff take a turn and on Tuesday it’s me. I start with the beds, then brush the carpet and finish up by tidying his desk.’

For some reason this turned on the waterworks and we had to pause for a minute or two.

‘I’m sorry sir, it’s just the thought of it… Mr Tom is — was — very fussy, you know and didn’t want us messing about with his papers, only to put them neatly into piles where he left them. I was at the desk, and I could see out of the window and across the side lawn. It was such a lovely day I couldn’t stop myself from looking out for a few minutes. I wasn’t slacking sir, honest I wasn’t. If only it had been raining then none of this might have come about. Mr Tom wouldn’t have been outside and his mother wouldn’t…’ She sniffled and I was certain she’d open the sluice gates again.

‘Hold on, Marion, let’s stay with what you saw out of the window.’

There was more sniffling and a blow of her nose before we could resume.

‘As I said, sir, I was by the desk, and looking out of the window at Mr Barleigh out on the lawn. He sat in his wheelchair reading most days when the weather was good enough. Always very fond of his books he was, sir, even before his accident.’

‘You were here before that happened?’

‘Oh yes, sir, though I hadn’t been here long then, a great shock to us all it was, especially to Lady Isabelle. She seemed to worry about him all the time after he came back from the hospital.’ The maid looked like she was going to tell me more but caught herself and returned to my earlier question. ‘Sorry, sir, I was telling you what I saw. Suddenly the blackbirds pecking for worms took off and Lady Isabelle came into view, from the front gate I think, though I couldn’t be sure. I straight away thought something must be wrong, ’cos her ladyship seemed to be shouting and waving her hand about like she’s half mad.’

‘What about the other hand?’

‘The other hand? Well, I think she must have had the shotgun under her arm because she was holding something close to her side.’

‘Did you see the shotgun, Marion?’

‘No, I didn’t. But that’s what it must have been, mustn’t it, otherwise where would she have got it from?’

‘That is something quite else. You remember what I said, and tell me what you actually saw, no more and no less. Understand? So what happened next?’

‘Mr Tom looked up at her — I didn’t see no more, sir, because Miss Parry, the housekeeper, had been watching me from inside the doorway and shouted for me to get on with my work.’

‘So you didn’t see the actual shooting take place?’

‘No sir, can’t say as I did. I heard the shotgun go off right outside, and Miss Parry and I both looked at each other but before we can do or say anything, there’s a second shot. We were then so terrified, sir, honest sir. Miss Parry tells me to go back up to my room, quick as I can, and she heads off down the stairs to look for Mr Jervis. I…’ She stopped, blushing.

‘What is it, Marion? Remember, this is a police matter, we need the complete truth.’

‘Yes, sir, Mr … Inspector. Well … truth is I didn’t go straight back upstairs. I crept back across the bedroom and peeked out of the window. It was only for a second, ’cos I couldn’t face it no longer, but what I saw was the two of them, Mr Tom and his mother, lying on the ground with the shotgun beside Lady Isabelle.’ She stared sightlessly ahead, remembering. ‘There was just the wheels of his chair going round and round…’

‘Did you see anyone else there, Marion?’

‘No, sir. All I could do was stare at those bodies. The blood and the stillness all around. There was no-one else there that I saw.’

The maid seemed transfixed by the memory and I had to prompt her to continue.

‘It’s all I know really, sir. I ran up to my room and stayed there until Miss Parry called all the staff together to tell them what had happened.’ Suddenly she looked at me, her eyes focusing. ‘Why’d she do it, sir? They were so close, the two of them.’

‘Well, that’s what I’m here to find out. Where were you when the third shooting occurred, that of Miss Bamford?’

‘Just where I said, sir. Miss Parry had called all the servants together in the kitchen to tell them what had happened. She was shaking like a leaf and said there’d been a terrible accident. A minute after she told us Mr Jervis had phoned the police there was another shot, from upstairs.’

‘Who was in the kitchen at the time, Marion?’

‘Well, sir, apart from me and Miss Parry, there was Mrs Veasey, she’s the cook, Peggy Shaw, the other maid, and Mr Perkins, the head gardener.’

‘So there were five of you, is that correct?’

Clark slowly counted the names in her head and on her fingers to confirm the number. ‘Yes, sir, that’s it.’

‘Mr Jervis and Nurse Collinge weren’t there with you?’

‘No, sir, they weren’t. Mr Jervis had been waiting for Miss Bamford to come back and someone said Nurse Collinge was too upset to come down. She was very fond of Mr Barleigh, you know.’

‘Had you seen Jenny Bamford arrive back at the house?’

‘I hadn’t, sir. As I told you, I went to my room like Miss Parry had told me and stayed there until she called for us to the kitchen. I don’t know when Miss Bamford came back, sir.’

I spent another few minutes clarifying some of the points she’d made and I underlined a couple of items in my notebook, then told her she could go. There was still something niggling me about what she’d seen that didn’t seem right.

Intrigued? Get A Shadowed Livery now and keep reading!

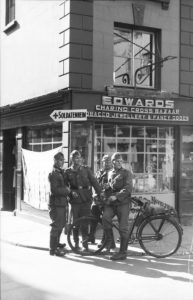

Following the publication of Deborah Swift’s extraordinary wartime sagas – PAST ENCOUNTERS and THE OCCUPATION – editorial director Amy Durant has signed four more of her books.

In Deborah’s words:

“I’m really thrilled to have signed with Sapere Books for my third WW2 novel, THE LIFELINE, in which a teacher flees Nazi-occupied Norway and escapes to Scotland on a small fishing boat, in an operation known as The Shetland Bus.

“Not only that, but I’ve signed with Sapere for three more historical novels set further back in time. The first, THE POISON KEEPER tells the story of Giulia Tofana, the woman who, according to legend, poisoned six hundred men in 17th Century Italy. The deadly poison Aqua Tofana bears her name. Italy in the 17th Century is a fascinating brew of baroque religion, art and culture, and the legacy of the ‘Camorra,’ the 17th Century Mafia. THE POISON KEEPER is set in Naples under the smoking shadow of Mount Vesuvius. There will be two further books in the Italian series; the other two books will be set in Venice and Rome.

“I was delighted to be offered a home for four new books (four books!) with Sapere, as not only do they offer very good royalty rates to authors, but they have a really strong, supportive author community.”

Amy commented: “Deborah is a wonderful storyteller, and I am extremely happy she has chosen to continue partnering with Sapere Books for her next four novels. Fans of her first two Second World War novels won’t have to wait much longer for her third wartime-era book; THE LIFELINE will be available to preorder soon.”

Click here to order PAST ENCOUNTERS

Click here to order THE OCCUPATION

Sign up to Deborah’s newsletter to stay up to date with her book news and latest releases.

Stephen Taylor is the author of A CANOPY OF STARS, a thrilling historical 19th century saga stretching from the legal courts of Georgian London to the Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt.

Hi Stephen! Welcome to the Sapere Books blog. Could you tell us a bit about what first got you into writing?

My addiction has been with me for over twenty years now. When I was younger, if somebody told me a good joke, when I retold it it was twice as long, embellished, the story enhanced, the characters fleshed out. With me, it was never just about and Englishmen, an Irishman, and a Scotsman. It was an Englishman in a bowler hat with a monocle, an Irishman in a donkey jacket with a pint of Guinness and a Scotsman in a kilt with a set of bagpipes (and yes I know that this is stereotypical).

Tell us about where you write and your writing habits.

I started by writing during my lunchtime at work, but now I write in my home office. I keep a working week, Monday to Friday and write for two and a half hours a day. I seem to need that discipline.

What part of the writing process do you find most difficult?

Probably research: it’s a double edged sword — part good, part tiresome. The rewrites are also tricky, as you can edit forever, endlessly trying to improve what you have written. I aim to stop after five rewrites.

Do your characters ever seem to control their own storyline?

The received wisdom is that you determine your storyline and not let your characters deviate from that. However, after I develop my characters, they tell me where they want to go, what they want to do. I follow them, and my stories are character led. I still have a structure in my mind — A to B, but the characters say how I get there.

Do you find it hard to know when to end a story?

Not usually. I have a prompt to myself that sits just below the line I am typing. It reminds me to keep some control over the characters. It says: INTRIGUE — CONFLICT — CLIMAX — RESOLUTION. i.e:

Open with a big question or hook: INTRIGUE. Then you have the problems your hero is up against: CONFLICT. This builds to a CLIMAX. This is followed by the RESOLUTION.

What is your favourite book?

If you ask me this next week, you may get a different answer. I would say my favourite book is To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee. My favourite character is Uriah Heep, from David Copperfield. Dickens’ image of him is wonderfully unpleasant — he’s so slimy.

What book do you wish you had written?

Anything by Norman Mailer. As a writer, he is so far above me. He’s much more than a storyteller.

Tell us something surprising about you.

I was brought up in Manchester, but I was born in Yorkshire. My mother traveled back to Yorkshire so that my birth there would give me residential status to play cricket for Yorkshire — nobody ever believes that, but I promise that it’s true. Unfortunately, it was a feat that I never achieved, the White Rose County being unappreciative of my cricketing skills.

Preorder A CANOPY OF STARS here!

Sign up to our newsletter for deals and new releases.

We recently had a digital meet-up with some of our authors to catch up on current projects and find out how lockdown has impacted their writing. Read on to find out more about their creative news and practices:

Elizabeth Bailey has published six Lady Fan Mysteries, four Brides By Chance Regency Adventures, and two more historical romances. She is working on her seventh Lady Fan book. Elizabeth has also been taking daily walks, giving digital readings, and maintaining her weekly newsletter, which is filled with writing updates and giveaways.

Graham Brack has published six Josef Slonský Investigations and two Master Mercurius Mysteries. He is working on the next books in both series. Graham finds that working on two series simultaneously helps prevent him developing writers’ block with either one.

Jane Cable has published one contemporary romantic saga drawing on World War II, and her second – Endless Skies – is forthcoming. Jane has been developing a new website, editing Endless Skies, and working on a new contemporary romance novel.

Tim Chant has a Russian-Japanese naval novel forthcoming and has started the next one. He is also writing and self-publishing science-fiction and steampunk novellas.

Michael Fowler has published five DS Hunter Kerr Investigations. He is currently working on a new series, developing a character who is a forensic psychologist. As part of this, Michael is researching various forensic technologies and has spoken to an expert in the field.

Michael Fowler has published five DS Hunter Kerr Investigations. He is currently working on a new series, developing a character who is a forensic psychologist. As part of this, Michael is researching various forensic technologies and has spoken to an expert in the field.

Justin Fox has two nautical novels forthcoming with Sapere Books. These are also being published in South Africa by Penguin Random House and are currently being edited.

Anthony Galvin (who also writes as Dean Carson) is the author of historical non-fiction book Death and Destruction on the Thames in London. He is working on a series of thrillers. As a mature student, Anthony has also been finishing up assignments and exams.

Sean Gibbons’ gritty crime series – following taxi driver Ben Miller – will be published in 2021. He is currently writing the fourth book in the series and has just finished a World War II espionage thriller.

Gillian Jackson has published three psychological thrillers. She is now editing old and self-published work, finding ways to re-purpose old characters. Gillian is particularly interested in developing more contemporary women’s fiction with a psychological element.

Natalie Kleinman has four Regency romances signed up and has written two more. She has recently made a start on a new romantic novel.

Simon Michael has published five Charles Holborne Legal Thrillers, and he has a sixth one lined up. Aside from writing, he has recently been busy with building work.

Ros Rendle has six romance novels forthcoming with Sapere Books, including her Strong Sisters trilogy. Ros has recently finished a new novel, and she has found her Chapter writing group (regional groups of romance writers affiliated with the Romantic Novelists Association) a great source of support.

Linda Stratmann has published five Mina Scarletti Mysteries and is writing the sixth. To help with this, she has been researching Victorian spirit photography using Archive.org. Linda has also been gardening, cooking, baking, and holding digital meetings with the Crime Writers’ Association, of which she is the chair.

Deborah Swift has published two romantic World War II sagas and is working on the third, which will be set in Shetland and Norway. She has been researching nautical terminology and walking a lot, which she finds is a great time to think about plot.

Alexandra Walsh has published three timeshift conspiracy thrillers; the last one, The Arbella Stuart Conspiracy, came out in May. She is now writing a Victorian dual-timeline novel and is planning to start a newsletter.

We are thrilled to announce that we have recently welcomed three brilliant new authors to our contemporary romance and historical fiction lists. We look forward to sharing their wonderful work with the world!

Tim Chant is working on an exciting historical naval thriller series. The first instalment – THE STRAITS OF TSUSHIMA – is set in 1905 during the Russo-Japanese war and follows the daring exploits of Marcus Baxter, a British Royal Navy officer turned spy.

THE STRAITS OF TSUSHIMA is due out in 2021.

Teresa F Morgan is working on a fabulous three-book contemporary romance series. Set in Cornwall, her novels have a strong sense of place and a unique sunny charm. Her first book, COCKTAILS AT KITTIWAKE COVE, sees ambitious restauranteur Rhianna Price arrive in the area looking for a fresh start. But when she runs into her holiday fling, Rhianna’s focus is put to the test…

COCKTAILS AT KITTIWAKE COVE is due out in 2021.

Tanya Jean Russell writes heart-warming romantic fiction. Her first book will be a seasonal novel called AN IMPERFECT  CHRISTMAS, a moving and uplifting tale that follows Maggie Green, a young accountant who returns to her hometown and is forced to face her first love.

CHRISTMAS, a moving and uplifting tale that follows Maggie Green, a young accountant who returns to her hometown and is forced to face her first love.

AN IMPERFECT CHRISTMAS will be published in late 2020.

Jane Cable is the author of ANOTHER YOU and ENDLESS SKIES, modern romantic sagas that draw on the Second World War.

Although I hated history at school, in my adult life I have become a total history buff. Not history about royalty, wars and politicians though – the history of ordinary, everyday people. A history I feel connected to and is more often than not local.

For my contemporary romances the history I choose is sharply focussed, linked to the setting. For Another You, the most gripping part of Studland’s past was its role in the practices for D-Day, and for Endless Skies I decided to stay with World War Two. The book is set in Lincolnshire, so to my mind is inextricably linked with Bomber Command.

The wartime setting for Endless Skies is RAF Hemswell, now an industrial estate best known for its antiques centres and markets. In fact, that was the reason I went there in the first place. But wandering around the old barrack buildings, I could almost see the airmen on the stairs and hear the stamp of their boots in the parade ground. This had to be the place.

The staff at Hemswell Antique Centres were able to give me a leaflet with a short history of the base, and that set me off on my research. While we were in Lincolnshire I walked its buildings and roads then drove around the area, so I was totally familiar with the terrain, and once we were back at home I started to dig deeper.

The staff at Hemswell Antique Centres were able to give me a leaflet with a short history of the base, and that set me off on my research. While we were in Lincolnshire I walked its buildings and roads then drove around the area, so I was totally familiar with the terrain, and once we were back at home I started to dig deeper.

Here the internet is invaluable, and there are a number of websites giving the history of RAF bases. Hemswell was one of the first to be operational right at the beginning of the war, but as I dug deeper I found two Polish squadrons had been based there in 1942-3 and had suffered huge losses. I knew exactly where to focus my research.

This is where local history becomes exceptionally localised for me: one place at one point in time. In Endless Skies my protagonist, Dr Rachel Ward, is an archaeologist and my own work made me think of hers: researching a site, carrying out a survey, opening a trench, trowelling into every corner then digging out a single artefact. She finds … well, it would be spoiling the story to tell you. I find words.

Hemswell War Memorial

But sometimes before you focus down you need to pan out, so I read around the subject: first-hand accounts from wartime bomber crews; memoirs of civilian life on RAF bases. For background on Hemswell itself I was very lucky – it was where The Dam Busters was filmed in the 1950s, and there was both a book and documentary about making the movie so I could watch almost contemporary footage.

There was also a treasure trove on the internet about the Polish airmen who crewed the station, and seeing photographs of them was quite an eerie experience. In fact, I ended up with far more information than I could possibly – or would want to – use in the book. But the level of detail gives me confidence my historical details are correct.

But equally interesting to me were the ghost stories associated with Hemswell: a pilot in flames on the runway, the echoes of 1940s music and the sounds of bombers taking off and landing. And having researched them, it would have been such a shame not to use at least one of them as well. Although my ghosts, of course, are completely fictional.

Click here to order ANOTHER YOU.

Click here to pre-order ENDLESS SKIES.

Keith Moray is the author of the SANDAL CASTLE MEDIEVAL THRILLERS, historical murder mysteries set in Yorkshire. The first two books in the series, THE PARDONER’S CRIME and THE FOOL’S FOLLY, are available to pre-order.

I live within arrowshot of the ruins of Sandal Castle. As a family doctor in Yorkshire, for thirty years I saw it most days while driving around the area on my morning visits. Nowadays, in semi-retirement I go running around the old battlefield where thousands of knights and soldiers once fought and died during the Wars of the Roses.

I plot and daydream when I run. Happily, a short story entitled The Villain’s Tale about a miscreant in a rat-infested dungeon in Sandal Castle won a Fish Award. It spurred me on to start plotting the Sandal Castle Medieval Thrillers.

Sandal Castle

The fine old motte and bailey was built in the 12th century by the De Warenne family during the reign of Henry I. From the 14th century it passed into royal ownership and is best known for its involvement in the Battle of Wakefield in 1460, when Richard, Duke of York was mortally wounded. His son, King Edward IV established it as one of the two bases for the Council of the North in 1472. Effectively, this was the government for the North of England. After he died, his younger brother, King Richard III began rebuilding the castle in 1483. The work stopped when he lost his life at Bosworth Field in 1485.

Thanks to television and movies, most people associate the outlaw Robin Hood with Sherwood Forest and Nottingham. However, the medieval ballads say that his stomping ground was actually Barnsdale Forest, which once covered a vast swathe of Yorkshire. The ballads also mention King Edward and various Yorkshire characters, such as George-a-Green the Pinder of Wakefield, and many actual locations in Wakefield are referred to.

The Court Rolls of the Manor of Wakefield

In medieval times, The Manor of Wakefield was the largest in Yorkshire and one of the largest in England, covering some 150 square miles. The Court Rolls of the Manor of Wakefield are a national treasure, consisting of a continuous recording of court proceedings from the late thirteenth century until the 1920s.

The outlaw and bowman Robert Hode, a sure candidate for being the historical Robin Hood, is mentioned in the Court Rolls of 1316.

The Sandal Castle Medieval Thrillers

If you look at the picture of Sandal Castle today you will see exactly where I had the germ of the idea for The Pardoner’s Crime, the first novel in this series. It is a view of the castle from under what I fancifully call Robin Hood’s tree. I blended historical facts, medieval ballads and a good deal of imagination to come up with a historical whodunit.

If you look at the picture of Sandal Castle today you will see exactly where I had the germ of the idea for The Pardoner’s Crime, the first novel in this series. It is a view of the castle from under what I fancifully call Robin Hood’s tree. I blended historical facts, medieval ballads and a good deal of imagination to come up with a historical whodunit.

There are three completed novels and a fourth in the pipeline. They are not all about the same characters; indeed they are set at different times, because Sandal Castle with its fascinating history is the historical backdrop to them. They are all inspired by Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and some of the characters that he described so beautifully. The Pardoner’s Crime fuses The Canterbury Tales with the Robin Hood legends. The reader is challenged to uncover the true villain in each novel.

Click here to pre-order THE PARDONER’S CRIME.

Click here to pre-order THE FOOL’S FOLLY.

Sandal Castle image credit: Keith Moray

David Field is the author of the Carlyle & West Victorian Mysteries.

As a historical novelist in search of bygone eras to recreate, I’ve always been fascinated by the late Victorian period. It was a time of contrasts, with vast scientific, medical and technological breakthroughs coming at a time when ordinary folk were obsessed with communicating with the dead. Victoria seemed destined to rule forever over a rich empire, while her subjects in its industrial cities, and most notably in its London capital, were existing in conditions of abject poverty.

Following the success of my Esther & Jack Enright mystery series, which began with the search for Jack the Ripper and ended just as the nineteenth century was about to, I was urged to return to this rich seam of inspiration, and there was – for me, at least – one obvious place to start.

When Arthur Conan Doyle abandoned medical practice and created his fascinating character Sherlock Holmes, he was inspired by his memory of a real life Sherlock. His name was Dr Joseph Bell, and he had taught anatomy to his classes of medical students at Edinburgh University, one of whom had been Doyle himself. Bell had what was then a unique approach to his analysis of the cadavers that were to be found on his mortuary slab, something that is second nature to modern forensic examiners, but was revolutionary in its day. He approached ‘cause of death’ by examining, not just insides of the bodies, but the clothing and personal possessions with which they arrived, and telltale indications on the skin, such as needle marks, abrasions, rough working hands and suchlike. From this he made logical deductions that were of value to police in unexplained death enquiries, and he taught his students to apply the same techniques when they went out into the world.

There must have been several generations of medical graduates from Edinburgh who were taught ‘the Bell method’, and it was no great stretch of the imagination for me to create Dr James Carlyle, anatomist and general surgeon at Whitechapel’s London Hospital – a medical doctor with the same professional training as Conan Doyle and the same inquisitive, logical mind as Joseph Bell.

His first challenge – described in the first novel in my new series, INTERVIEWING THE DEAD – is to debunk the panicked belief among the populace of the East End that the spirits of those buried in a Plague Pit in Aldgate have returned to take their revenge for the disturbance of their resting place. That belief has taken hold easily, given the obsession with Spiritualism that gripped the country during this period.

But there were also other ‘spirits’ abroad, and they were advocating for great social change. Chief among these were the Suffragists, who campaigned for ‘votes for women’ and Suffragettes who took on entire police forces in public demonstrations. There were also other groups of feminists, as we would call them today, who advocated for equality of admission to professions such as medicine and the law. This was how Dr James Carlyle’s daughter, Adelaide, was created, as a young woman whose opinion of men and their dominance of society could not have been any lower – until she meets my third new character, Matthew West.

Although the Anglican Church was ahead of all other Protestant movements in the 1890s, it was demonstrating a social elitism that drove away ordinary working folk, and left the pastoral door open for more working-class religious initiatives and crusades among the poor. ‘Methodism’ had become a religious movement of its own, with its own hierarchy, but its progenitor, ‘Wesleyism’, still had its head above the parapet, and Wesleyan street preachers such as Matthew West might be found on corners, in market places, and outside factory and dockside gates.

Matthew has his own reasons for wishing to hose down any belief in the return of vengeful spirits of the dead, and when he finds himself associated with Dr Carlyle in the search for the truth, he comes up against the fiery Adelaide, who works as her father’s assistant. They influence each other’s views on life as they are drawn imperceptibly into a mutual attraction.

The stage is set for my next series. I hope you’ll join me in following the exploits of this unlikely trio, and I look forward to learning your reaction to them.

Click here to pre-order INTERVIEWING THE DEAD!

Sapere Books has reached its second birthday!

We now have a family of over 50 authors and plenty of chart successes under our belt.

To celebrate our first two years as a company, we threw a party in London and caught up with our fabulous authors over drinks and nibbles. All have exciting new projects brewing. Here is a taster of what to expect from our authors in 2020.

Alexandra Walsh and Graham Brack

Graham Brack is working on a historical fiction series, the Master Mercurius Mysteries, set in the 17th century. The first book, Death in Delft is already available to pre-order, and more will follow later this year.

Keith Moray has written the Sandal Castle Medieval Thriller series, historical murder mysteries set in Yorkshire. The first book, The Pardoner’s Crime, is available to pre-order, and more are soon to follow.

Alis Hawkins’ brand-new Medieval novel The Black and The White will be published later this month.

David Field is working on a brand-new Victorian mystery series, the Carlyle & West Mysteries, which will launch very soon.

Jane Cable has another thought-provoking romance with echoes of the past launching soon.

Stephen Taylor, Caoimhe O’Brien, and Keith Moray

Gillian Jackson has written a new psychological thriller, which will be released this summer.

Natalie Kleinman will be joining our excellent Regency Romance authors with her sparkling new books, which will feature strong and resourceful heroines.

Ros Rendle will be launching her Strong Sisters series this year – sweeping sagas that will explore family relationships and rivalries.

Seán Gibbons’ gritty urban crime series set in Galway will launch later this year.

J. C. Briggs and Linda Stratmann

Stephen Taylor has a series of 18th century novels coming out soon.

And there are new books coming out soon from fan-favourite series, such as Alexandra Walsh’s Marquess House Trilogy, Elizabeth Bailey’s Lady Fan series, J C Briggs’ Charles Dickens Investigations series, Gaynor Torrance’s DI Jemima Huxley series, Charlie Garratt’s Inspector Given series, Michael Fowler’s DS Hunter Kerr series, Valerie Holmes’ Yorkshire Saga series, Marilyn Todd’s Julia McAllister series, Simon Michael’s Charles Holborne series, John Matthews’ Jameson & Argenti series and Linda Stratmann’s Mina Scarletti series.

For more information on our latest releases and ebook deals sign up to the Sapere Books newsletter.

To celebrate International Women’s Day (8th March) we asked five of our authors to tell us all about their favourite female writers. Read on to find out more about their literary heroines!

Alis Hawkins, author of The Black and the White and Testament

My all-time favourite author is Joanna Trollope. An odd choice for a crime author? Not at all. Wonderful writing transcends genre, and she inspires me by drawing characters with a fine eye to dialogue and interaction; by bringing whole scenes to life with a few telling details; by making her readers care passionately about what happens to her characters.

Joanna Trollope has shown me how essential it is to do your research meticulously, to immerse your readers in the world you’re writing about – whether it’s a cathedral close or a dairy farm, a ceramics factory or a Spanish vineyard – but never to include a single unnecessary fact that might slow the action down.

Each Joanna Trollope novel begins with a single key event that turns the lives of all her interrelated characters upside down – and what else does a murder at the beginning of a book do but that?

Order THE BLACK AND THE WHITE here

M. J. Logue, author of the Thomazine and Major Russell Thrillers

My busy little mind raced over all the possibilities – Tanith Lee, Storm Constantine, Dorothy Dunnett, Helen Hollick … but there can be only one, for me. Aphra Behn, of course. It’s not the what or the how of her writing, but the enigma and the old-school glamour of the writing persona she created – the international woman of mystery, the myths with which she surrounded herself – that inspires me. (Three hundred and fifty years later, she’s still a mystery!)

My busy little mind raced over all the possibilities – Tanith Lee, Storm Constantine, Dorothy Dunnett, Helen Hollick … but there can be only one, for me. Aphra Behn, of course. It’s not the what or the how of her writing, but the enigma and the old-school glamour of the writing persona she created – the international woman of mystery, the myths with which she surrounded herself – that inspires me. (Three hundred and fifty years later, she’s still a mystery!)

She was the first female literary professional, she did all her own publicity, and she’s still incredible. Possibly a spy, possibly bisexual – both, I suspect, images she manipulated to the hilt – and definitely a woman who knew how to work an audience. The fact that her plays and poems still resonate with us now is remarkable. She created characters that speak to us, no matter what clothes they’re wearing.

Or find out more about the Thomazine and Major Russell Thrillers here

Deborah Swift, author of Past Encounters and The Occupation

The first Rosie Tremain novel I read was Music and Silence, set in the Danish court in the early 17th Century. Marvellously atmospheric, it shifts between different narrative styles: small vignettes that add up to a magnified version of life in Copenhagen that is so real, you feel you are there.

I’ve read all her other books since, including the more contemporary The Road Home, about an economic migrant arriving in the UK, who observes with bafflement the English obsession with status and success. I admire Tremain’s precision, and that is something I want to achieve in my own writing.

Gaynor Torrance, author of the DI Jemima Huxley Thrillers

I write in the genre I love to read, and being an avid reader of crime fiction, there are so many female authors whose work I admire. A particular favourite of mine is Sophie Hannah. I first stumbled across her books by chance, when I borrowed a copy of Little Face from my local library. Once I started reading, I couldn’t put it down.

I write in the genre I love to read, and being an avid reader of crime fiction, there are so many female authors whose work I admire. A particular favourite of mine is Sophie Hannah. I first stumbled across her books by chance, when I borrowed a copy of Little Face from my local library. Once I started reading, I couldn’t put it down.

Since finishing that particular book, I’ve worked my way through much of the Culver Valley Crime series. I adore the originality and complexity of Sophie’s plots, which have lashings of intrigue and misdirection. The central characters, DS Charlie Zailer and DC Simon Waterhouse, are such a great pairing. They’re both so dysfunctional and vulnerable in many ways, yet somehow form a compelling and likeable team.

Or find out more about the DI Jemima Huxley Thrillers here

Alexandra Walsh, author of The Marquess House Trilogy

She may be old-fashioned, and her comments can make me wince, but take away the occasionally dubious contents of a bygone era and Enid Blyton remains a huge inspiration with the breadth of her storytelling skill. In her adventure books, her plotting is deft and sharp, while in her fantasy books her imagination is broad and tantalising.

As a child, she shaped my reading habits but my eureka moment came when I was reading In the Fifth at Malory Towers. I was already harbouring ambitions to be a writer, but it was only a dream. Then, the heroine of the series, Darrell Rivers, wrote the school pantomime. Suddenly, I thought, If Darrell can do it, then so can I! My life path was set. From reading Enid Blyton’s work, I learned that girls were stronger and more effective if they worked together, that girls could do as much as boys and usually more, and that if you were determined you could solve anything – lessons that still resonate today.

Order THE CATHERINE HOWARD CONSPIRACY here

Or find out more about The Marquess House Trilogy here

Jean Stubbs is the author of the INSPECTOR LINTOTT INVESTIGATIONS series and the BRIEF CHRONICLES series. In celebration of her life and work, we asked her daughter, Gretel McEwen, to share her memories of Jean and her writing.

We lived in a world of stories, the line between reality and fiction often blurred. As a child, my mother had always made up plays and stories — her brother an unwilling but worshipful bit part player. A generation later, my mother made up fictional characters for my brother and I — she brought them to life with special voices and we talked to them. Alfred was a gentle and not very bright giant whose answer to any question was 29!

My mother had her first novel, The Rose Grower, published at the age of 35 and from that moment our house was filled with a whole cast of characters. I came home from school one day to find her weeping over the death of Hanrahan (Hanrahan’s Colony). And the hanging of Mary Blandy (My Grand Enemy) brought very dark clouds into our house.

As my mother surfed her way through this creative theatre, we learned to read the signs — coffee cups on every surface, a sink full of dishes and no plans for supper meant a good and productive writing day. A house full of the smell of baking, a gleaming kitchen and rice pudding in the oven either meant the dreaded writer’s block or a completed first draft. So we too surfed, adjusted and gloried in the passing show. My mother always wrote on our vast Edwardian dining table, and her writing companion was always the current much-loved cat. They had their own specially typed title page upon which to sit, since she had learned the hard way that cats like to sit on the top copy with muddy paws! The mystery cat was the black one who sat on a certain stair — but when you went to stroke him he was not there … another blurred line…

I felt closely involved with each novel as it progressed. At the end of a good writing day, my mother would read aloud to me the latest chapter — a fine reader with a different voice for each character, once more bringing it all to life. She wrote in long hand at first, then, as the book grew, she typed chapters then full copies and carbon copies for her publisher, Macmillan. Later, she was one of the early authors to use a word processor. When the first print draft came from the publisher, we would sit at each end of the dining room table and proofread — calling out corrections to each other and marking them on the manuscript.