Ellen Tyrell’s Nose and Other Suspicious Circumstances

With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

I am looking for a drowned girl. My old friend, Professor Swaine Taylor will, no doubt, provide the grisly forensic detail in his Medical Jurisprudence: ‘the eyelids livid, and the pupils dilated; the mouth closed or half-open, the tongue swollen and congested … sometimes indented or even lacerated by the teeth …’

I need an inquest on said drowned girl; this is where the British Newspaper Archive comes in. There are drowned girls aplenty in London in the decade 1840-49. Poor things, dragged from the Thames, the Regent’s Canal, the Surrey Canal, the New River, the Serpentine, the lake in Regent’s Park, from under Waterloo Bridge – a favourite spot for those seduced and abandoned girls. There they lie stretched out on muddy shores and banks, their bonnets askew, one boot missing, or both, their faces pale like Millais’ Ophelia, or more likely, bloated and bruised, or half-eaten by decomposition – or rats. Their bodies sometimes float, buoyed up by petticoats – the effect of air retained by the clothes, or the presence of gases. Sometimes a thin hand grasps a clump of weed which, according to Professor Taylor, indicates that the victim went into the water alive. Did she fall or was she pushed? Suicide, most often.

I find the case of the suicide of two young sisters dragged from a Leeds canal in April 1847, tied together by a handkerchief. The handkerchief is pitiable somehow, and memorable. Dickens must have read of that case for he uses the same circumstance in Our Mutual Friend. Something of a thrill in contemplating that, but I need only one girl.

I need an unknown drowned girl, unclaimed, buried at the expense of the parish, and forgotten. Somewhere in a village, a mother wonders about her lost child. She will never know what became of her ruined darling. The Morning Post in February 1842 explains: ‘In London the bodies are taken to any obscure vault, public house, or police office. The Coroner directs the parish to advertise the body, often in vain.’

I find several cases of unidentified females in the newspaper archive. In July 1841, according to The Morning Advertiser, a young woman was pulled from the London Dock. She was never identified. I am intrigued by the report’s dark observation that ‘No one could walk into that water by accident.’ Unknown, too, is the identity of the ‘fine-made ’young woman taken from the Serpentine in October 1845 and deposited at St George’s Workhouse. Yet she has a distinctive mole on her left cheek, dark hair and hazel eyes. Surely somebody missed her. Seduced and abandoned, perhaps, like poor Eliza Luke found in the New River in April 1844.

However, this is a crime story, so, naturally, I need a drowned, unknown, murdered girl. This is more difficult. Such is the damage done by the water, or the bridge, or the rocks of some lonely reach that it is often impossible to find enough evidence of murder. However, there is the case of Eliza Rayment found in the River Thames in October 1847. There is a deep cut under her chin. Four inches in length, an inch in depth, so reports Mr Bain, the surgeon, at the inquest, and there are ‘two arteries divided’. The wound might have been inflicted by the deceased, but ‘a person using the right hand would naturally make an incision on the left hand side.’ Eliza Rayment was right-handed. Mr Bain attributes death to the loss of blood from the wound. Poor Emma Ashburnham who was formerly Emma Meyer had once lived ‘in some splendour’ in York Road under the protection of ‘a gentleman of fortune’, but it is not known how she came to be in the river at Waterloo Bridge with a deep and ugly stab wound in her side.

Blood brings me to Ellen Tyrell and her nose. Ellen was found in the Surrey Canal in August 1845. Mr John Hawkins, the surgeon, finds an abrasion on the right side of the nose, but from the decomposition of the body he is unable to distinguish any other external marks of violence. Given that she was seen in the company of a man, not her husband, the night before she disappeared, the inquest is adjourned for the purpose of producing further evidence.

Oh, Eliza Rayment, what a mystery, what a suggestive tale, a married woman whose whereabouts were unknown for some days before your death. Who were you with? Emma, who was that ‘gentleman of fortune’? Alas, neither of you is for me, and Ellen, your nose, telling though it is, does not serve my purpose. I am ‘Oh, that I had been content with a cut throat, or a stabbing, but, in the interests of my plot, the victim must be strangled or I must rewrite the whole damned thing.

There is evidence I do like: the 1847 case of the unknown drowned young woman wearing a false plait at the back of her hair; the one in 1842 in which an umbrella is found nearby, bearing on its ivory handle the initials ‘F.H.’ And I like especially, the single earring she is wearing. I have a fancy for a single ruby like a drop of blood in my victim’s ear.

I dig deep into the newspaper archives and I find it – just the one, and the indefatigable Mr Bain is on hand to assist. The body was found in October 1848 near Battersea Bridge, much decomposed, appearing to have been in the water some time. Nevertheless, Mr Bain finds evidence of a ligature encircling the neck, though what this might have been he cannot say.

It is quite enough for me. Possible death by strangulation.

Oh, all right, I admit it: the body was that of a sailor. But, it did happen. Evidence of a ligature was found. I’ll just have to put an ‘s’ before the ‘he’. No one will know.

‘F.H.’? Names: Fanny? Florence? Flora? Ah, here’s a name in the archives: ‘Harvest’. I have her: Flora Harvest, the Grim Reaper cometh.

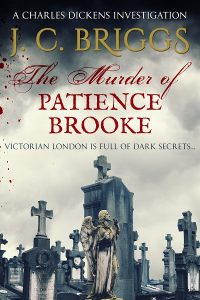

The Murder of Patience Brooke by J. C . Briggs